Di = two, ode = way. So diode = two way.

Diodes were originally called rectifiers because of their ability to allow current to flow through them in one direction but not the other. Before solid state electronics, we had valves (thermionic vacuum tubes, thermionic valve) although it appears that the solid state diodes and the valve version were actually developed around the same time. Perhaps valve technology was easier to implement, or more stable, or cheaper back in the early 20th century.

The thermionic valve has a sensible name. There are many different types of valves in fluid pipes; some are just taps that manually permit or stop fluid flow. Others allow fluid to flow in only one direction. The word valve comes from the Latin valva, which means door (or more specifically, the moving part of the door). Most doors only open one way when pushed, so this is a sensible name to give a component that allows current to flow in just one direction. The word thermionic has an interesting etymology.

Thermionic does not come from thermal ionisation. Although electrons are emitted by the thermionic effect, leaving behind the absence of negative charge, the electrons that are emitted were already delocalised, and the metal already contained ions held together by those delocalised electrons in the conduction band. So, confusing thermionic emission with ionisation is understandable but still incorrect.

Thermionic emission was discovered before JJ Thomson discovered the electron in 1897. It was discovered several times independently by different physicists, but Thomas Edison (perhaps the seventh person to discover the effect after Edmund Becquerel, Frederick Guthrie, and others) has the honour of having the effect named after him. Perhaps less common now, but thermionic emission was called the Edison Effect in the early 20th century.

The particles that were released from a metal’s surface when the metal was at a high enough temperature were originally called thermions. Thermo is the Latin for heat. The greek word ion meant go. (Cation means ‘down go‘. Anion means ‘up go‘. More on this later). The convention became for particles to be named with the suffix ‘ion‘, or later just ‘on‘ (proton = proto + ion = first go). So thermions were ‘heat go‘ particles because they moved away from the high temperature surface. There’ll be more on the etymology of ion later.

Thermionic valve was a very sensible name for the device that used the thermionic effect to allow current to flow in just one direction. So where does the word diode come from?

Naming conventions in electricity and magnetism

In the early days of electromagnetism, before the discovery of the electron, naming conventions had to be decided. In the mid 18th century, Benjamin Franklin decided that, when rubbed with fur, glass charged positively and amber charged negatively. He adopted the word charge as an analogue for financial transactions. He visualised the situation like this: when rubbed, the amber lost some sort of electrical currency, which was gained by the fur. When the glass was rubbed by the fur, the glass gained the electrical currency and the fur lost it. The same amount of electrical currency moved from one material to another in contact. This solved the conundrum of why there were two different effects that could be observed with charged bodies: attraction and repulsion; charges had two flavours. He could have named them up and down, black and white, in and out, top and bottom, or any pair of opposites, but being an economist he decided to call them charges and label them positive and negative, assuming that something becomes negatively charged when it loses electrical currency and positively charged when it gains electrical currency. Negative charge wasn’t a thing in itself, just a debt of electrical currency.

So much for charge. Current was defined as the rate of flow of this charge. Around 1820 Hans Christian Ørsted discovered that electric currents affect magnets. Electric currents have their own magnetic fields around them. This means two parallel current carrying wires experience a magnetic force between them. This is how the unit of current (the Ampere) was originally defined, using Ampere’s Law. Current was known about, measurable, and understood in terms of the flow of positive charge.

What about electrodes? If charge flows towards or away from an electrode, what should it be named? Even the word electrode had to be coined.

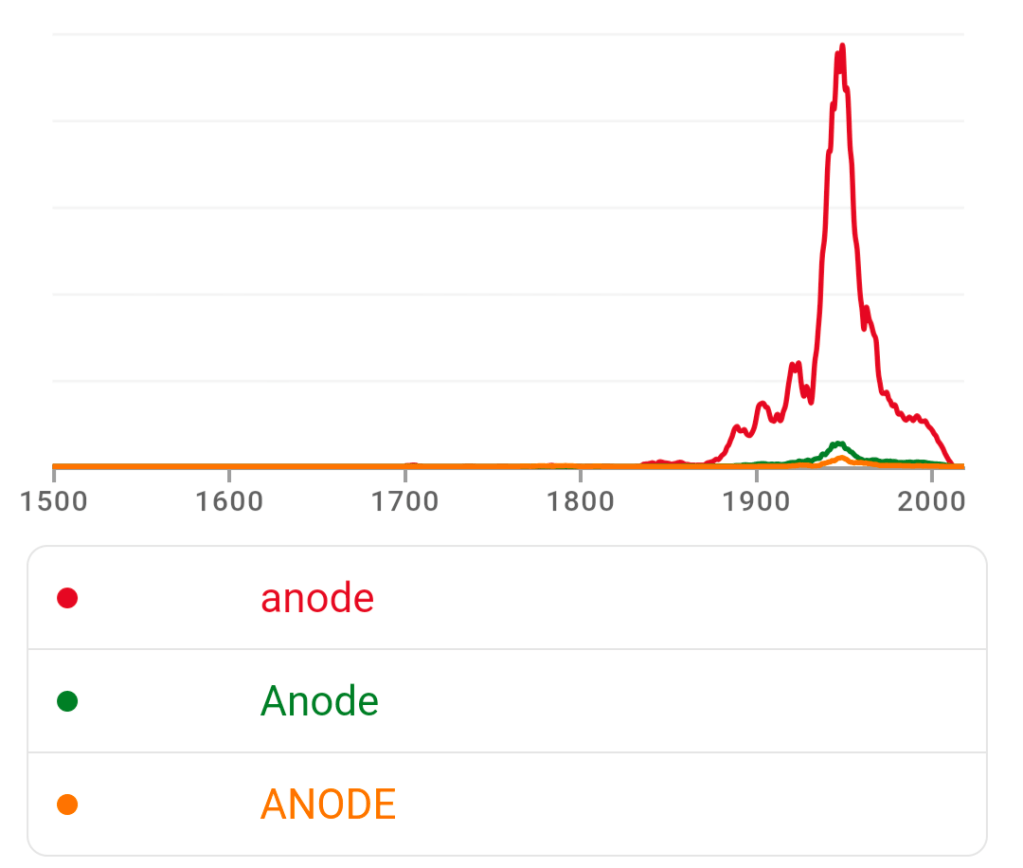

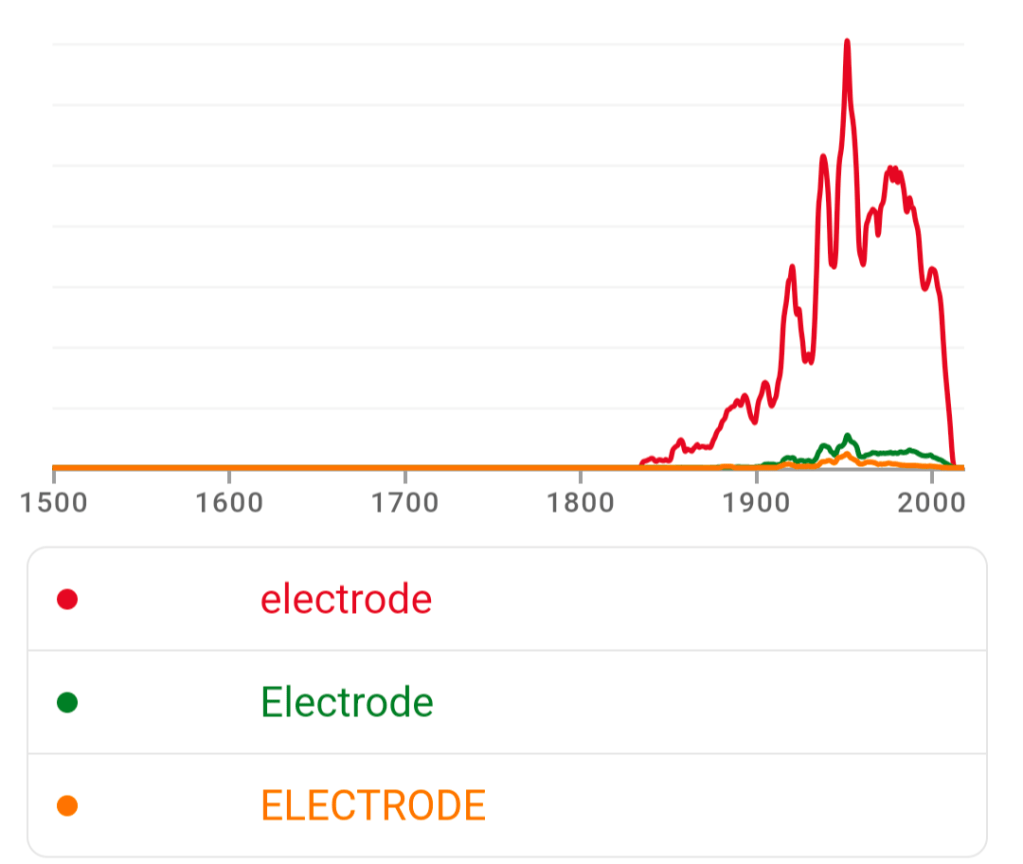

Electrode comes from electricity + ode (hodos, but shortened to ode). The word electricity in English has existed since the early 17th century, used to describe the phenomenon of attraction towards charged amber, which had been first observed by the ancient Greeks. The Greek word for amber is electron. The word electric had existed in English since decades earlier. The subatomic particles called electrons were so named because it was discovered that they were the particles moving when a body is charged by friction, so the particles were named after amber because they had the same charge as amber (negative, thanks to Benjamin Franklin). Interestingly, and perhaps confusingly, the word electrode was coined before the discovery of the electron! So what about hodos (or ode) for way? Where does that come from? And what about the an- and cat- prefix?

After the discovery of the relationship between electric currents and magnetic fields by Ørsted in 1820, naming conventions were needed. Currents could be produced by chemical reactions between a solution and two different metals, causing the flow of particles, which we now call ions, but which way the particles flowed in the solution was a mystery at first. Magnetic fields already had a naming convention. Magnetic fields emerge from the north pole of a magnet and recede into the south pole of a magnet. This naming convention, it turns out, is a bit backwards. The north seeking pole of a compass (which is just a small magnet) points towards the geographic north pole, hence its name. Over time, this name got shortened from ‘north seeking pole’ to just ‘north pole’. But to be attracted to the geographic north pole, the geographic north pole has to be a magnetic south pole. Whoops. Nevertheless, the naming convention stuck, and so we have magnetic field lines going from north to south around magnets. It was discovered that the magnetic field around current carrying wires form concentric circles, so no north or south pole there.

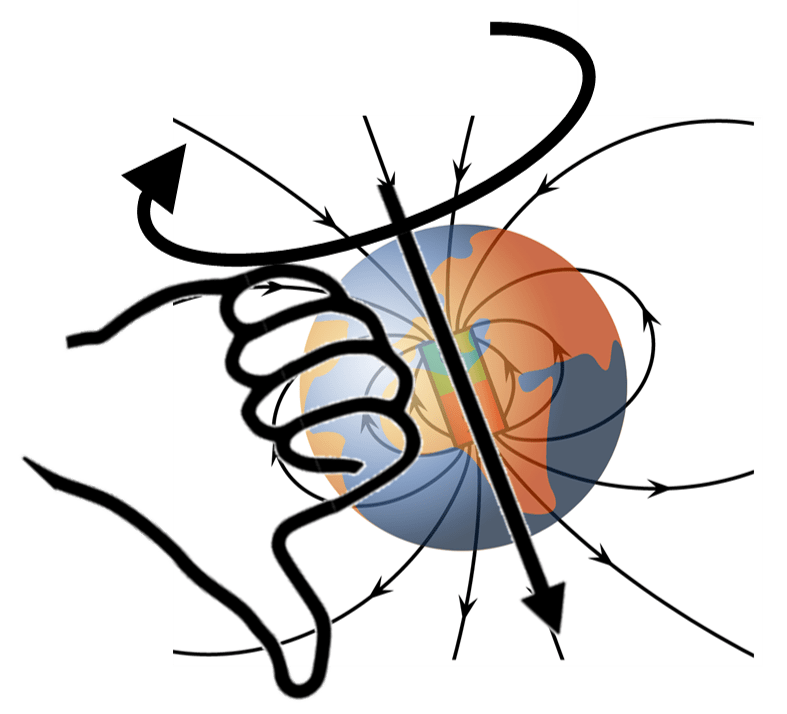

A loop of current carrying wire, however, produces a magnetic field shape similar to a bar magnet, with magnetic field lines emerging from one side of the loop (the north side) and moving around to enter the other side of the loop (the south side).

To get current to flow around the loop of wire a battery is needed – or at least some sort of chemical reaction on each end of the wire, one oxidising and one reducing. Oxidising reactions remove electrons from the atoms in the solution, reducing reactions add electrons to the atoms in the solution. Where oxidation happens, electrons are coming out of the solution and going into the wire, making that end of the wire more electrically negative. Where reduction happens, electrons are being added to the solution from the wire, making that end of the wire more electrically positive.

The voltaic pile, named after its inventor Alessandro Volta in 1799, was the first electric battery. With the voltaic pile, currents could be produced in wires consistently (a constant direct current, or DC, could be produced). The electron had still not yet been discovered! The direction of flow of charge through a wire was still assumed to be from positive to negative, using Benjamin Franklin’s convention. So what about the direction of flow of ions within the solution? It was observed that reaction products were deposited on the metals within the solution.

This is where the link between electric currents and magnetic fields becomes important in inventing a naming convention. Consider the following analogy. From the surface of the Earth, there is a north pole and a south pole, and the sun rises in the east and sets in the west as it moves around the earth. I know this sounds a bit geocentric, a bit Ptolemaic, but it’s an analogy used to come up with a naming convention, which we still use today, so go with it. From the middle of a coil of current carrying wire, there is a north pole and a south pole, and current flows around the coil in a particular direction.

In our analogy, the sun represents the flow of charge (assumed to be positive electric currency). Using the right hand grip rule, and remembering that the magnetic south pole of the Earth is near the geographic north pole, and the magnetic north pole of the Earth is near the geographic south pole, if you align your thumb with the Earth’s magnetic field through the earth, the fingers curl in the direction the sun moves across the sky. Try it! Right hand thumb pointing down (south), fingers curling east to west. So the end from which the positive charge flows could be called east, and the end to which the positive charge flows could be called west. Just as the sun flows from east to west, so charge flows from east to west. Sensible.

However, as it stands the north-south naming convention is problematic because the magnetic poles’ names are the opposite to the geographic poles’ names, so if a convention was chosen where the east and west were not reversed – or even if a convention was chosen where they were reversed – it could cause confusion. To avoid this, the word up was chosen instead of east, and the word down was chosen instead of the word west. The sun goes up in the east and down in the west, so we now have an up pole and a down pole for electric currency. The Greek word for up was ana, and down was kata. Rather than referring to the ends of the wire connected to the voltaic pile as poles, a term that was to be reserved for magnetic fields, the greek word for road/route/way was chosen, hodos. So the east pole became the up way, or the ana hodos (which became anode), and the west pole became the down way, or the kata hodos (which became cathode). The general term for one of these electrical routes in a solution became electrode (electricity way).

Cathodes are often negatively charged and anodes are often positively charged, but not always. As long as there are two electrodes at different potentials, the most highly positive electrode will be the anode and the most highly negative electrode will be the cathode, regardless of their charges (4V is more highly negative than 8V in the sense that it is further along the number line in the negative direction, -4V is more highly positive than -8V in the sense that it is further along the number line in the positive direction).

Remember the Greek word ion, meaning ‘go‘, used to refer to particles moving through the solution? Particles that moved towards the down way (the cathode) were called down going particles, kata ions, or cations. Cations flow towards the cathode. Particles that moved towards the up way (the anode), were called up going particles, ana ions, or anions. Note that the prefixes an- and cat- have nothing to do with negative and positive, but to do with the direction of flow, and that anodes and cathodes are not always positive and negative respectively.

Back to diodes. The convention of calling an electrical connection to a solution in electrolysis an electrode had been established. The suffix -ode came to mean an electrical connection. When thermionic vacuum tubes started to be developed, different designs were invented. Some had two electrical connections, some three, some four. The Greek for two was dis (shortened to di), three was treis (shortened to tri), four was tettares (shortened to tetra). Vacuum tubes with two connections were called two-ways (diodes), tubes with three connections were called three-ways (triodes), tubes with four connections were called four-ways (tetrodes).

Thermionic valves were vacuum tubes with two connections, they were diodes. When solid state rectifiers became more prolific, they were referred to as diodes after the vacuum tube they replaced, and the name has stuck.