Students often choose to study A-Level Physics because they want to understand how the universe works. GCSE Physics has lots of gaps, but surely Advanced Level Physics will have the answers? Here are five intriguing mysteries that A-Level Physics does not answer. If you think you know the solution to any of these, comment below!

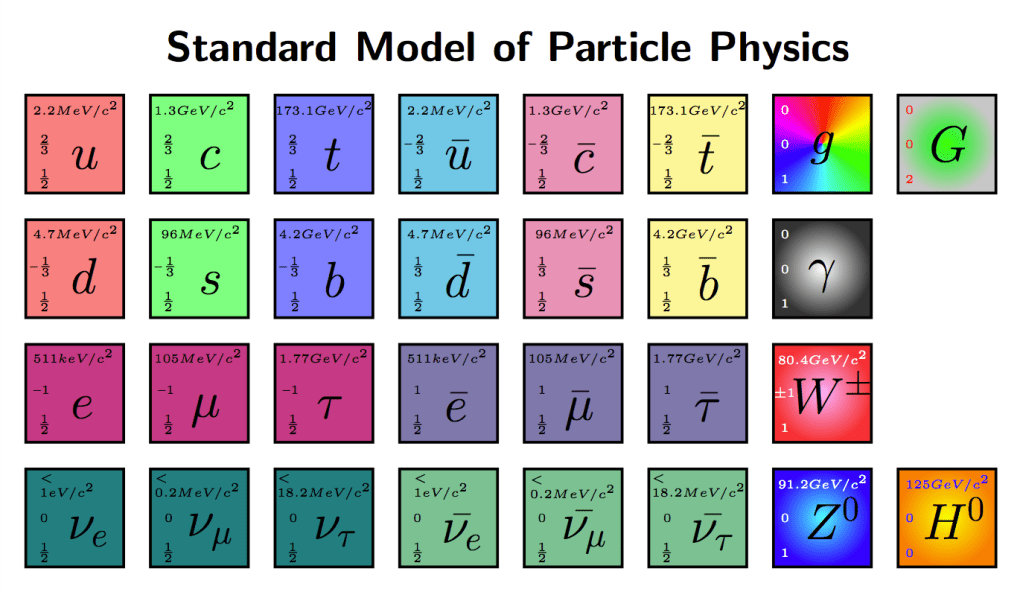

1. Why do three quarks make a unit of charge?

Up, charm, and top quarks have +⅔e charge. Down, strange, and bottom quarks have -⅓e change. The reason why you cannot get isolated quarks and that they form stable particles in threes (baryons) is because of the strong nuclear force, which acts between colour charges. Quarks have colour charge, electrons do not. Electrons do not experience the strong nuclear force. So why do electrons have exactly three times the charge of a down quark? Or why does a down quark have exactly ⅓ of the charge of an electron? The force that ensures quarks must be in threes does not apply to electrons, but each quark has an integer multiple of ⅓ the charge of the electron. How does the electric know to have thrice the charge of a down quark, or is it a cosmic coincidence?

2. Where is all the antimatter?

When a high energy photon decays, it produces a pair of particles with mass; one is matter and one is antimatter. In high energy proton-proton collisions, quarks and antiquarks are produced in equal numbers. In all particle interactions that we learn about, the conservation rules are clear: matter and antimatter balance. So, why is the universe almost entirely matter? Where is all the antimatter? Why should matter be special?

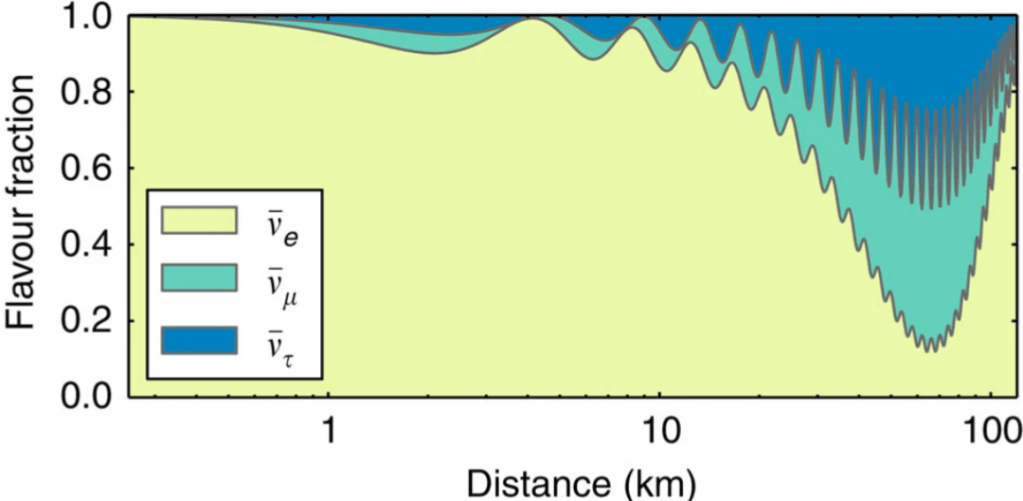

3. Why do neutrinos oscillate generation?

Neutrinos are leptons, and we know lepton number must be conserved separately for each generation of lepton. Electrons do not spontaneously change into muons, nor vice versa. Muons can decay into electrons but only but only by the emission of two neutrinos: a muon neutrino and an electron anti-neutrino. So given this important conservation rule, why are equal proportions of the three generations of neutrinos detected from the Sun? Only first generation neutrinos should be produced in the fusion reactions in the Sun, but we detect second and third generation neutrinos. The theory is that they cycle through different generations why they travel, but why should they? And how do they do this? And going back to muon decay, how can three particles be emitted (the electron, muon neutrino and electron anti-neutrino) at exactly the same time, or is there an instant when the conservation rules are broken? What are neutrinos anyway?

4. What is gravity?

Two popular pictures exist. One involves exchange particles between massive particles. The hypothetical exchange particles are named gravitons. Much like virtual photons, the direct detection of these would weaken the force. Virtual photons cannot be detected, but real photons can. Are there virtual gravitons and real gravitons? If not, why not? If so, why haven’t we detected real gravitons yet?

The other picture for gravity involves visualising a stretched rubber sheet, and saying that mass distorts the rubber sheet. In this picture, the rubber sheet represents spacetime, and the distortion of spacetime causes a smaller mass to accelerate towards the larger mass. Usually this picture is used to show that a planet will follow a curved bath because spacetime is curved by the presence of the Sun. However, in the picture used to teach this, the reason the rubber sheet curves is because of gravity, and the reason the smaller mass follows a curved path is also because of gravity. Trying to explain gravity by using a model that requires gravity to work is problematic.

5. Why does light refract as it passes from air to glass?

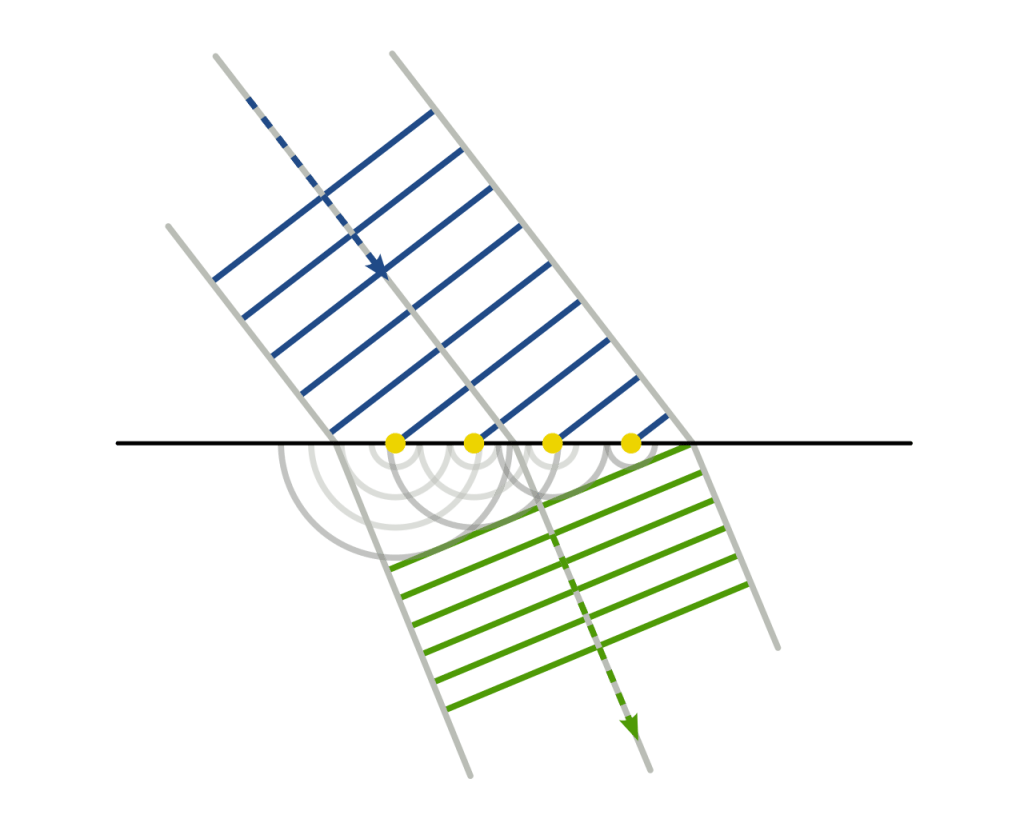

GCSE students learn that light slows down in glass, and that causes a ray of light to change direction as it passes from air to glass. At A-Level, we derive Snell’s Law and can confidently calculate the refraction angle for light. We have an idea that refractive index is a measure of the degree to which light is slowed down. We might even touch on Fermat’s Principle (light travels between two points following a path that takes the least amount of time), and we will certainly learn the Huygens-Fresnel Principle (each point on a wavefront is the source of a spherical wavelet, and the superposition of an infinite sum of wavelets infinitesimally separated will produce the next wavefront). Both of these principles are good pictures and can be very useful, but neither really answers the crucial question; why does a ray of light change direction. Why questions are always more challenging to answer! But perhaps an even more fundamental question should be asked: why does the light slow down in glass? What is the mechanism for refraction, and what material properties can be used to calculate refractive index?

Conclusion

A-Level Physics is a broad and deep subject, but some of these questions cannot be answered because of the complexity of the answer, or simply the limitation of time for teaching. Yet, some of these questions cannot be answered for a different reason: we do not know the answer. Which of the five questions listed in this post do you think physicists cannot yet answer, and which do we fully understand but just cannot teach during the A-Level course? Comment below!