Black holes are celestial entities so dense that nothing can escape them – not even light. There are five classifications of black holes:

- Micro black holes: these are tiny. Their diameter is less than a fifth of a millimetre, but their mass is too up the mass of the moon. In 2001 it was proposed that these could form in particle colliders but only if the universe had extra hidden dimensions (such as is proposed by string theory). These would quickly decay, emitting a jet of particles in the process.

- Stellar black holes: these have the diameter of a county, about 60km, and have masses comparable to the mass of stars, from two to one-hundred and fifty times the mass of the sun. Because these form by the gravitational collapse of a dying star, they’re sometimes called ‘collapsars’, although that can also refer to white dwarfs if the mass of the stat is below 1.4× the mass of the sun.

- Intermediate-mass black holes: as the name suggests, this category sits between stellar black holes and supermassive black holes. In 2004 the first intermediate-mass black hole was discovered.

- Supermassive black holes: these have one-million to one-billion times the mass of the sun, and so can have enormous diameters from around 0.2% the distance between the Earth and the sun to 10 times the average diameter of the orbit of Pluto. These are thought to be found in the centre of almost every large galaxy.

- Ultramassive black holes: this term is not widely used, but some astronomers use it to describe even larger black holes, with some astronomers even having a category larger than this called ‘stupendously large black holes’.

Given what black holes are (regions with huge density), why are they called ‘holes’ at all? If I were baking a cake and it did not rise evenly, and a region in the cake was left far denser than the regions around it, I certainly would not refer to that dense region as a hole.

One basic way to understand black holes is to say that their escape velocity is greater than the speed of light. This idea is usually introduced at A-Level when escape velocity is taught. The escape velocity of the Earth is about 11.2 km/s; so ignoring air resistance, a body travelling vertically upwards with an initial speed of 11.2km/s will never fall back to Earth. If the initial speed were any slower, then the body would eventually fall back to Earth. Actually it’s not as simple as that, because the Earth is itself accelerating as it orbits the Sun.

The escape velocity of Jupiter is nearly 60km/s. Jupiter is more massive, so bodies must have a higher initial speed to escape. In this classical physics approach, the density of a body that would have an escape velocity greater than the speed of light can be calculated. If light cannot escape the body, nothing can – or so the simple explanation goes; however, this is not quite true in classical physics.

Rockets leave the earth without having a minimum initial speed of 11.2km/s. Now it’s true that not all rockets escape Earth’s gravity because they usually end up orbiting the Earth, but some go on to travel further. In the case of the Voyager and Pioneer probes, much further! The rockets carrying those probes travelled nowhere near as fast as the escape velocity of the Earth initially. So how did those rockets escape Earth’s gravity? They burned fuel. They carried a chemical energy store, which was transferred to the kinetic energy store of the rockets as they ascended. The ascent transferred energy from the kinetic energy store to the gravitational potential energy store, so were it not for the fuel, the rockets would slow, stop, and then fall back.

With the classical understanding of black holes (bodies with escape velocities greater than the speed of light), there would be no reason why a rocket carrying sufficient fuel could not fall into a black hole, and then blast its way out – except that the nearest black hole is too far away for us to reach, so we wouldn’t be able to test this even if we did think it was true. Which we don’t.

So what are black holes really? A better definition can be found using general relativity. A black hole is a region so dense (of such high energy-momentum tensor) that a geodesic from inside the black hole simply loops back into the black hole and cannot connect with any point in spacetime outside a black hole.

A geodesic is a straight line in Minkowski space (basically four-dimensional spacetime). A line that is straight in Minkowski space can appear curved in our three-dimensional quasi-Galilean perception of space. In Minkowski space, the ‘distance’ (given as a four-vector, not a three-dimensional spatial vector as we are used to using for distances) between two events is the same regardless of the apparent motion of an observer of the two events, whereas the ‘distance’ (the three-dimensional spatial vector we perceive using quasi-Galilean mechanics) between two events will be different if observers are moving with different velocities relative to the events. That can be quite complicated. I have referred to quasi-Galilean because our everyday perception of reality looks Galilean to us, but in fact it is Lorentzian. Even using Lorentzian mechanics, we would perceive different three-dimensional distances between events if observing them at different relative velocities, but the distance between the events in Minkowski space would always be the same. Transformations of co-ordinates of events into Minkowski space is done using Lorentz transformations, not Galilean transformations, which is why I’ve referred to three-dimensional space measurements as quasi-Galilean. I thought it was simplify things, but I was ostensibly wrong. A geodesic is a straight line in Minkowski space, that is the important point from this paragraph.

If a geodesic passes through a point in spacetime within a black hole’s event horizon, there will be no point along that geodesic outside the event horizon. The geodesic will form a closed loop. Light follows geodesics, so light would simply loop around forever and ever inside a blackhole, because there is no path leading from inside to outside.

Consider a geodesic some distance away from the event horizon outside a black hole. Here, the geodesic is straight in Minkowski space, but appears curved to us. Light follows geodesics, so light appears to bend around black holes for this reason. I could simplify all this by saying gravity deforms spacetime, but perhaps that could lead to further misconceptions (see my post here: five things A-Level Physics does not answer).

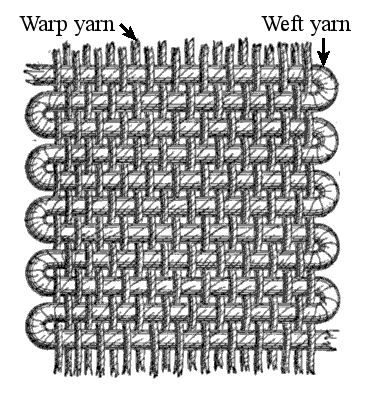

Now, let us visualise a sheet of cloth, made by weaving threads together. The threads are given two names depending on their orientation. The ironically named warp threads are held in place while the weft threads are woven between them, to create a sheet of cloth. Any reference to warp in this article is to do with cloth threads, not to do with a science fiction plot device to make spacecraft travel between two points in space faster than light could travel. Imagine taking a pair of scissors and cutting a circle in a sheet of cloth. There would be no connection between the warp threads within the circle and the warp threads outside the circle. Anyone reasonable would say that I have cut a hole in the cloth. Similarly, there is no connection between geodesics inside the event horizon of a black hole and outside, so anyone reasonable would say that spacetime itself has a hole in it.

Some of you are now scratching your heads. If there is no geodesic going from inside to outside a black hole’s event horizon, then how can there be geodesics going from outside to inside? How can light enter a black hole along a geodesic, but there then be only looped geodesics inside the black hole? A fine question!

The short answer is, it is not as simple as I have suggested. Geodesics can be future-pointing time-like vectors or past-pointing time-like vectors. There can be past-pointing time-like vectors going from inside to outside black holes, and future-pointing time-like vectors going from outside to inside. Now you know what to search for if you want to learn more.

The reason black holes are appropriately named is because they are discontinuities in spacetime, they are holes, not just very dense bodies.