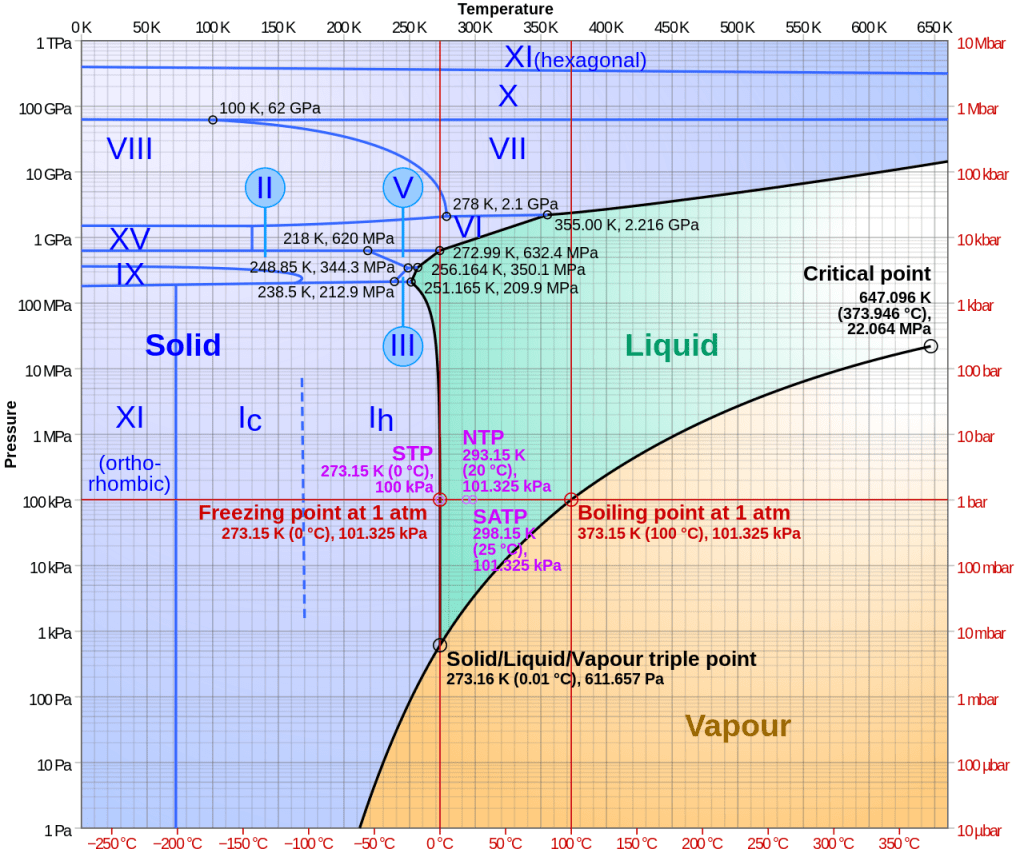

When you cool pure water steam at atmospheric pressure from a temperature above 100°C, energy will continue to be removed from the steam at 100°C whilst its temperature does not change. The steam will be changing into liquid water. If we then continue to cool the liquid water, when it reaches 0°C energy will continue to be removed from the water without reducing its temperature further until the water is frozen into ice.

The energy that is removed from water steam as it condenses is called the latent heat of vaporisation (or sometimes called the latent heat of condensation). The energy that is removed from the liquid water as it is frozen is called the latent heat of fusion (or sometimes the latent heat of melting). Side note: the term ‘specific latent heat’ means ‘latent heat per kilogram of substance‘, but exam boards often get that wrong.

So, that’s it right? I can remove energy now from the water ice until it reaches -273.15°C, and it will reduce temperature the whole time? Right?

Wrong.

In primary and secondary school you learn about the states of matter: solids, liquids, gases, plasmas. In material science, there are phases of matter. As a material moves from one phase to another, there is a latent heat of that transition, just as there is when a substance is taken from one state to another.

It turns out, there are at least nineteen phases of water ice (at the time of writing, the latest was discovered in 2021).

Each phase is a unique packing geometry of water molecules. Each phase has different properties, such as hardness and density. Transitioning from one phase of ice to another involves a transfer of energy that does not involve the kinetic energy stores of the molecules in the ice, it involves the potential energy stores.

The internal energy of a system is the sum of all the potential energy stores and all the kinetic energy stores. Changing the kinetic energy stores of a system manifests as a temperature change, because temperature is related to the mean kinetic energy per particle in the system. If the particles in the system are made to move faster on average, thus increasing the total kinetic energy stored, this will also increase the average kinetic energy per particle, and will be measurable on a macroscopic scale as an increase in temperature.

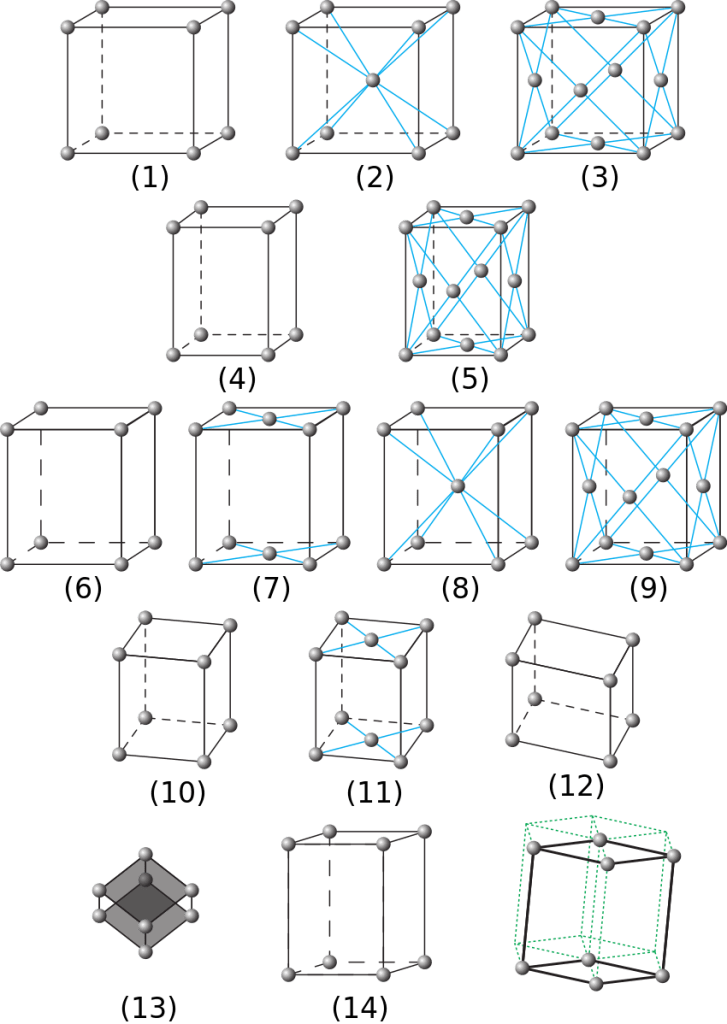

Any change to the internal energy of a system that does not cause a change in temperature is caused by a change in the potential energy stores of the particles in the system. The simplest type of change of potential energy store relates to crystal structure. Hexagonal crystals are more closely packed than simple cubic crystals, so the potential energy stores are lower, for example. There are other ways potential energy stores can be changed, such as changing the magnetisation of a domain. The element dysprosium has a magnetic phase change at low enough temperatures, for example.

What is fascinating is that there are fourteen unique Bravais lattices; fourteen unique ways to arrange the unit cells in a crystal, and yet so far there have been nineteen unique ice phases discovered. With a little thought, it’s easy to reconcile this apparent contradictions, but in the interest of trying to encourage a bit more interactivity, I’ll invite you to comment your thoughts on this below! 👇