I asked this question to my daughter (age 9) today, and she said there were too many to count. When I told her the correct answer, she thought for a moment, then responded with the familiar ‘aaaah’ of comprehension. She realised her mistake without needing any further scaffolding, and mistakes are healthy.

We learn by making mistakes. We cannot progress in our understanding without making mistakes. A student who never tries to answer for fear of making a mistake will progress far slower – if at all – then their more-engaged peers. Such a student may think they’re engaging because they’re thinking and making notes and fully concentrating, but if they’re not trying to answer questions where there is a genuine risk of them getting the answer wrong (and occasionally getting the answer wrong too) then they are not truly engaged.

Why must mistakes be made to learn? Because the world proliferates misconceptions, so if mistakes aren’t being made it means those misconceptions are not being challenged.

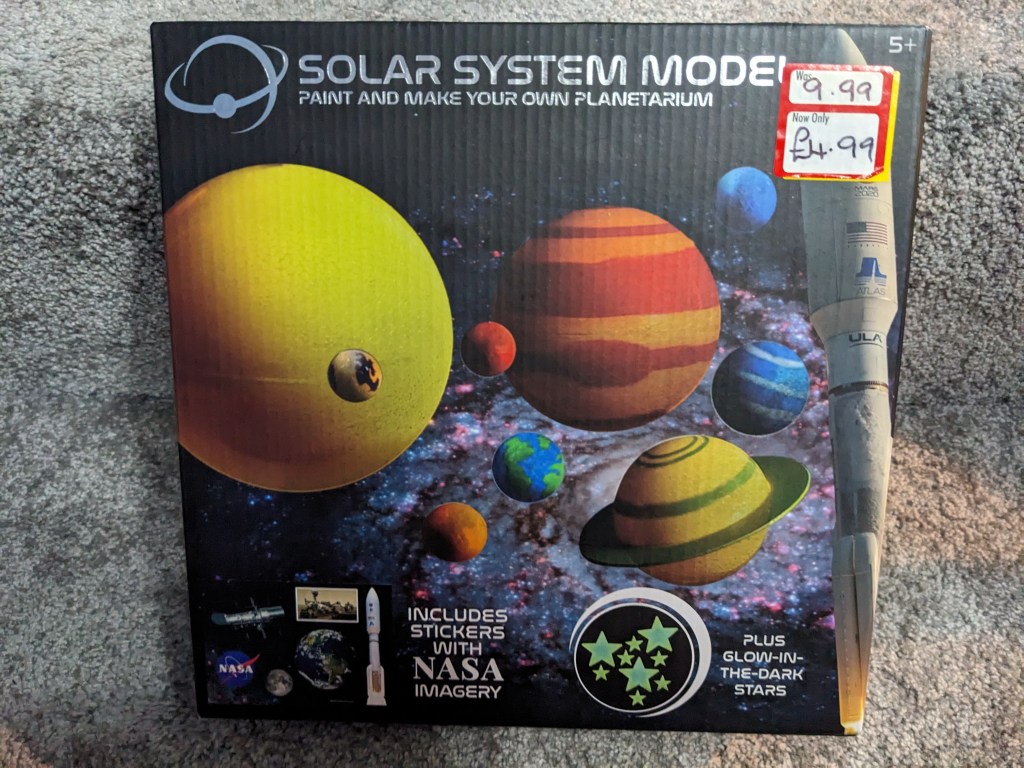

Consider this Solar System Model kit (pictured above). The planets and Sun are not at all to scale (but how could they be without it looking rubbish?) and it comes with eight large stars and twelve small stars. You can tell they’re stars because they’re star shaped, right? Well, no, stars are spheroidal. But stars viewed through reflective telescopes have spikes (diffraction spikes caused by the light diffracting around the spokes holding the small mirror in place), so that explains the star shapes, right? Well, no, because you cannot get five point diffraction spikes, that’s just not how diffraction works. I’ve no idea how we will decide which polystyrene sphere is which planet, given their nonsense relative sizes.

This kit is designed for 5+ year olds. They’ll feel a sense of pride when they’ve finished it, a satisfaction, an emotional response to the work that will help commit facts about the solar system to the child’s long term memory – we learn better when we have an emotional response to the material being learned. What facts are being learned? The facts presented in this model – most of which are incorrect. They’re misconceptions, not facts at all, and they need to be unlearned later. I reckon a big part of Key Stage 3 and Key Stage 4 physics is about unlearning misconceptions acquired from worldly experiences.

Ask most people to state any of Newton’s Laws of Motion and they’ll probably say something like ‘what goes up must come down’ (where did that come from?) or worse still, ‘every action has an equal and opposite reaction.’ (Many readers will now be scratching their heads over that statement being worse than the previous, but I’ll explain why that is the case in tomorrow’s post).

For as long as the world is teaching incorrect physics and astronomy (and other misconceptions from the lesser-sciences), there will be a need for teachers to correct them. For teachers to correct the misconceptions, the students will have to have sufficient insight – they need to realise for themselves that the misconceptions they’ve learned are not facts, but fictions. For students to come to such a realisation, they need to have their misconceptions challenged so they can test them against situations that highlight why the misconceptions are wrong. That means the students have to get things wrong to learn.

And there is only one star in the solar system.