Misconceptions, misconceptions everywhere. Yesterday I posted about how students pick up misconceptions from their worldly experiences, which we must challenge as physics educators. In this post I’m going to focus on a pet peeve of mine. I believe this is the number one misconception in physics.

It’s often worded as ‘every action has an equal and opposite reaction’, and viewed by the general public as a sort of physics karma. I’ve seen the phrase casually batted around in all sorts of situations, too many to list and I would not want to produce a list of incorrect applications of this phrase anyway. It is the reason I believe that what I’ve written above is the worst possible way of phrasing Newton’s Third Law.

This is better:

Forces between two bodies always come in pairs of equal magnitude and of the same type acting along the same line of action between two bodies in opposite directions simultaneously.

I know, that is a bit verbose. Let’s break it down.

Right from the start we are talking about forces. Not action (which is the integral of the Lagrangian with respect to time, the Lagrangian function is the kinetic energy of a system subtract the potential energy of the system. In general, people do not mean this action when they state Newton’s Third Law using the badly worded phrase).

Examining the wording closely, there are six conditions, six properties, six separate statements that can be made about forces involved in Newton’s Third Law:

1. There are two bodies interacting, therefore two forces between them, one on each body.

2. The two forces have equal magnitude.

3. The two forces are of the same type.

4. The two forces act along the same line of action.

5. The two forces act in opposite directions.

6. The two forces act at exactly the same time.

The first point is often forgotten, particularly by Hollywood. My biggest objection to the X-Men: First Class (2011) was not that Magneto could move metal without touching it – I can do that with magnets. No, my biggest objection is exemplified in the scene where Magneto moves the radio telescope (often erroneously referred to as a satellite dish). He pulls it with enough force to get it to twist around, but he remains unaffected. How?

The second and fifth points most people grasp fairly easily, and the fourth point is often vaguely understood, even if no real thought had been given to it. The sixth point is the one that’s neglected by those who apply the badly worded phrase to all sorts of unrelated situations. The sixth point is one of the reasons I detest the action/reaction wording; neither force is the cause, rendering the other the effect. Rather, both forces are as much cause and effect as each other. They both arise simultaneously.

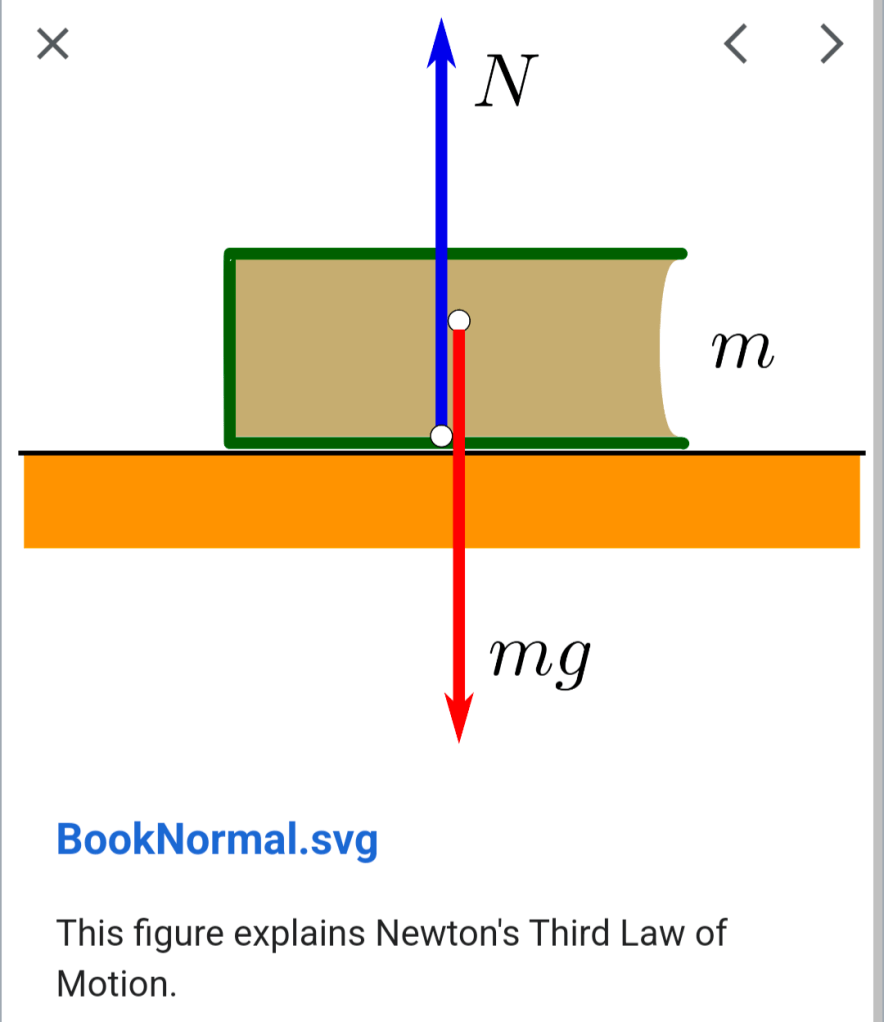

The third point is the one students most often forget, or perhaps fail to grasp. Consider the case of someone sitting on a chair. There is a force acting on the person from the Earth – the force of gravity. There is a force acting on the person from the chair. These two forces happen to be the same magnitude and are in opposite directions, but they are different types of forces (one is gravitational, one is a contact force). That means that they are not a Newton’s Third Law pair. The chair pushes the person up, the person pushes the chair down. That’s a Newton’s Third Law pair. The Earth gravitationally attracts the person down, the person gravitationally attracts the Earth up. That’s a Newton’s Third Law pair.

The formula to determine the pair force is easy: swap the nouns and reverse the directions.

[NOUN 1] exerts a [TYPE] force [DIRECTION] on [NOUN 2].

[NOUN 2] exerts a [TYPE] force [OPPOSITE DIRECTION] on [NOUN 1].

Dave exerts a push force left on a door. The door exerts a push force right on Dave.

Or another example:

A slotted mass exerts a pull force down on a spring. The spring exerts a pull force up on the slotted mass.

It works, and following this recipe will help you avoid confusing two forces for a Newton’s Third Law pair if they’re not. Better still, keep in mind the six conditions listed above.

The alarming thing is that it isn’t just students who get Newton’s Third Law wrong, and it’s not just the general public. When I started teaching in 2010 I heard of a school where none of the science teachers were physicists. Someone from the Institute of Physics was brought in to do some teaching training, and posed all of them a simple problem: “Draw a diagram showing a ball at its maximum height after being thrown in the air along a curved trajectory. On the diagram, show the forces that are acting on the ball.” All of the science teachers drew four arrows on the ball, and then encountered difficulties when they tried to label the types of force. They were convinced that there must be an upward force on the ball because there was a downward one. Despite all their experience teaching, none of them understood Newton’s Third Law. They also all drew a forward arrow because they also did not understand Newton’s First Law, but that’s a different story.

I’ve been the Head of Physics at my school since 2013 and in that time I’ve interviewed a lot of candidates for physics teacher positions. It is genuinely concerning how few understand Newton’s Third Law, and I will not recommend we appoint any physics teacher who does not understand such a fundamental concept (unless, of course, they’re very early in their career – everyone has to learn at some point. But if a teacher has lots of experience and still doesn’t understand Newton’s Third Law then that’s a problem).

The badly worded phrase for Newton’s Third Law is easy to memorise, but it causes misconceptions, so I believe it should be avoided. What does equal and opposite mean anyway? How can two vectors be equal but also opposite? Nonsense.