My ten-year-old daughter and I built a robot together back in 2020 when she was only six-years old. Today, she asked if we could build a robot again. Of course, I was happy to oblige.

She has done some simple circuit work at school, but didn’t really have any clear understanding of circuits (not that she does now). So, I got her to use a voltmeter to check which AA batteries worked. I have just asked her again what she did:

Me: “What did you use the voltmeter to check?”

My daughter: “I used it to check that the current was flowing.”

Yep, there’s more work to be done here 🤣.

She gets some credit for knowing that ‘current flows’, although when I pointed out that it is actually charge that flows to cause a current, she got a little confused. I can see why. She had some idea about the structure of the atom, because she’d read it in a book. She had heard of protons, neutrons and electrons, but wasn’t clear what was meant by charge. The electricity topic at her school is being taught with no reference to charge at all. I’m gobsmacked; how can anyone understand electricity if one has no understanding at all of charge?

Quoth my daughter, “we were taught that voltage flows in wires”. Maybe she was, maybe she wasn’t. A child’s memory isn’t always reliable. Let’s assume innocence and hope that her primary school teacher wasn’t teaching nonsense.

The word charge is a tricky one though. Like so many technical words in Physics, its meaning is entirely different to the colloquial meaning, and it’s even more complicated because the word charge is colloquially used in the context of electricity. I asked my daughter what she thought the word charge meant. Understandably, she related the word charge to what you do to phones and laptops; they don’t work if they’re not charged. Plug a wire into them to charge them. I pointed out to her that charging a battery (colloquial meaning) doesn’t charge the battery (physics meaning), but that just confused her more. When I talked about energy transfers, it cleared things up a bit, and she was happier with the idea that we store energy in batteries when we charge (colloquial) them. I describe charge to her a simply an property that electrons and protons have, and she then had a lightbulb moment where she compared charges to magnetic poles. Close enough at this stage, I thought. She’d made a connection between charge and electromagnetic forces, which is good enough at this stage. Neither I nor her primary school had talked about forces between two charges, she’d remembered that from her science books.

So much for current. We played around with this interactive PhET animation and I used the lumped element model to explain how charge moves around a circuit, transferring energy to components. She finally was able to answer questions about what current does in series and parallel circuits, and had clearly gained a better understanding of circuits – but for how long? Brains have a frustrating way of forgetting things, especially such abstract concepts as charge and current. Back to the robot.

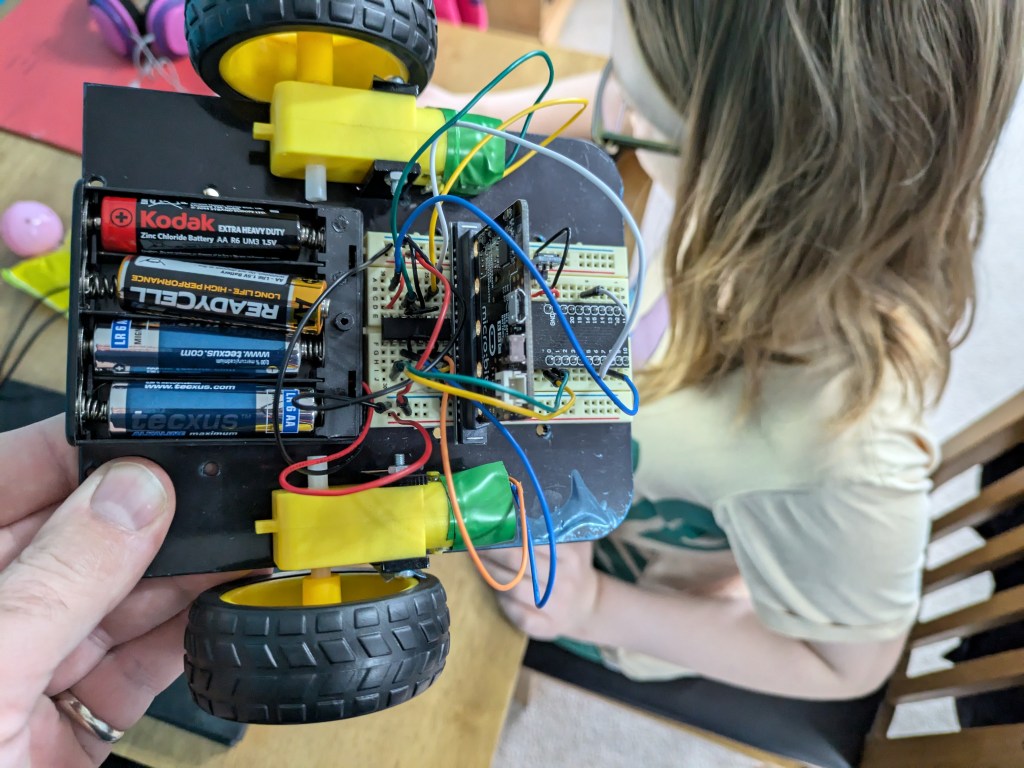

We used an L293D chip to drive two motors, but I couldn’t remember how to connect it, so I showed her how to search for a data sheet and how to interpret a pin-out diagram. With some encouragement, she connected the chip up to the motors all by herself.

For simplicity, we are using a BBC Micro:Bit to drive the robot, so I had to use a voltage converter chip. This was a good opportunity to talk to my daughter about different voltages. The BBC Micro:Bit is happy to be driven at 3.3V, but the motors really need a minimum of 6V.

I decided not to go into too much detail about voltage at this time. I don’t like teaching about voltage until I can get a clear run-up and teach electric potential first, and then electric potential difference. She had an idea of energy transfers in circuits (albeit with a flawed model, but a model that will work for now), but in my experience teaching voltage too soon after teaching current is a bad idea, and just serves to cause confusion between the two very abstract terms. Current and voltage are both ‘electricity‘ in the mind of a child, so care must be taken when teaching them to ensure the two quantities are kept separate and clearly defined. I’ll teach her about electric potential another day.

She wired up the robot all by herself (I told her what to do, but she did it) and tested the components herself too, but putting 6V on the correct pins on the L293D chip to get the wheels turning each way. She used an ohmmeter to figure out which pins on the BBC Micro:Bit breakout board were connected to the BBC Micro:Bit (because it can be connected either way to the breakout board), and chose which pins to use for the digital output from the BBC Micro:Bit to drive the L293D chip. I showed her how to use the BBC Micro:Bit pin diagram to find pins that were not used for other purposes (some pins are also connected to LEDs on the screen, for example, so you cannot really use them without having nonsense appearing on the 5×5 LED panel on the BBC Micro:Bit). My daughter built it and tested the hardware, I just told her what to do.

Then the coding started.

She has used Scratch before, so coding the BBC Micro:Bit by dragging and dropping blocks of code should have been easy. This is when my daughter revealed to me that, in her school, she uses Scratch during their ‘free time‘ to play games, because the other games are all blocked on the school network 🙄. Two things: firstly, why is there so much ‘free time‘ in Year 6 of primary school? ‘Free time‘ apparently happens every day when pupils complete the tasks set, and are allowed to do whatever they like on the computers. I’m not impressed by that – imagine if we did that in secondary school! Secondly, why is she not being monitored during this ‘free time‘ and being encouraged to be productive? There are online typing courses, online language courses, even using scratch for some actual coding would be a better use of ‘free time’. Rant over (for now).

Time to teach her some coding fundamentals by dragging blocks around.

“It’s like purple mash”, quoth she. She had used a website called purple mash to do some coding stuff before – during lockdown in 2020, when her primary school provided absolutely no work for her to do and we took control of her education. It’s been a few years, so much has been forgotten, but the jist of logically arranging blocks was still understood.

So that’s the progress of the robot so far. After one day (a couple of hours) she’s got the hardware built, tested, and coded to drive in different directions, randomly changing every second. The next step is to use a second BBC Micro:Bit to control the robot.

My plan is then to upgrade her to an Arduino, so that we can use ultrasound sensors (they can be used with the BBC Micro:Bit but it’s a huge faff because of the 3.3V the microbit uses. It’s been a while, but I recall last time I used the ultrasound sensors it was easier to just use an Arduino). All of that can wait. Right now, she’s happy to practice coding by moving blocks around.

I’ll update you all when she’s got it driving around, later this week (possibly Friday, or Sunday). After a couple of hours of electronics and coding and learning about current, she needed a break.

Reminder: Weekly Live Tuition Sessions!

SATURDAY 28th February 2026

| GCSE Physics | 9:30am | Motor effect |

| A-Level Physics | 10:30am | Electromagnetic induction |

| GCSE Astronomy | 11:30am | Formation of planetary systems (1) |

If you wish to enrol on the tuition sessions and haven’t yet, then click enrol below

My daughter’s robot works well! Next she wants to add a buzzer, controlled by pressing a button on the controlling BBC Micro:Bit. I’ve explained to her how transistors work. We’ll get to all that later, I’m sure.

LikeLike

She’s now added a buzzer, so I had to teach her how to use transistors.

LikeLike