The target audience of this post is teachers and parents who are supporting children with their physics education. Young people are welcome to read it (they may find it interesting) but it could cause extra confusion for all but the most capable students.

Brace yourself, this is a long post! (8325 words, estimated 44 minutes reading time)

All professionals have a responsibility to keep up to date with their field. In science teaching, we often are good at keeping up with changes and developments in pedagogy, but the science knowledge and understanding has not changed for a very long time, right? Actually, a significant change appeared on GCSE physics specifications in 2016 to be first examined in 2018, but many teachers did not notice it and I daresay most teachers are still teaching the old curriculum without realising it because that is what they were taught.

Energy is a tricky concept in physics. The concept is made trickier by the ubiquitousness of out-of-date or incorrect models.

The old model

Decades ago, schools taught that there were between 7 and 9 types of energy. A typical list might look like this:

- Gravitation potential energy

- Kinetic energy

- Elastic potential energy

- Thermal energy

- Chemical energy

- Nuclear energy

- Light energy

- Sound energy

- Electrical energy

In this older model, energy is transformed from one type to another by some sort of process. For example, when a ball falls, its gravitational potential energy is transformed into kinetic energy by the force of gravity. When a battery operated torch is used, chemical energy is transformed into electrical energy by the chemical reactions in the battery, and then electrical energy is transformed into light energy and thermal energy by the lamp.

The old model worked fine for a long time. It is the model I was taught at school. It is the model my teachers were taught when they were at school too. Generation after generation was taught this model. Text books and revision guides were written for this model. Exam questions tested it; the same legacy exam questions used in many schools to this day (including mine, but I really must look at updating that).

The model had problems though. Firstly, it gave students the impression that energy was a substance that flowed from place to place. Secondly, it got difficult to apply this model to situations such as bungee jumpers, where multiple transformations were happening at once. Thirdly, physicists and engineers track energy transfers (work being done, the processes and changes to a situation due to changing energy stores), which isn’t really compatible with the older model. What is sound energy anyway? Where is the sound energy? Fourthly, the older model encouraged and rewarded rote learning, not an understanding of the processes involved.

What the new model isn’t

The way energy is explained in many newer textbooks and revision guides reminds me of a story from 1998, when an exam board mistakenly invented the units ocrawatt for power and ocrajoule for energy. The exam board was OCR, who had just been formed after amalgamating a few localised boards, including the Midland Examining Group (MEG).

Clearly what had happened was OCR had simply used MEG’s physics syllabus, and replaced all instances of MEG with OCR using a find/replace function in the word processor, so megawatt became ocrawatt, and megajoule became ocrajoule.

The relevance of this story is that some folk seem to be doing the same thing when trying to teach energy, replacing all instances of energy ‘types’ with energy ‘stores’ and thinking that will do.

It is true that we talk about energy stores in the new model, not energy types, but we also talk about energy transfers. I teach these as energy transfer mechanisms, but the Institute of Physics and other sources use the term energy pathways. I take issue with the term pathway, for reasons I will explain later.

This splitting of the list of energy types into two different lists of energy stores and energy transfer mechanisms means that a different understanding is needed. One cannot just replace the word types with stores

The history of the new model

In Making Sense of Secondary Science by Rosalind Driver (1994) it was argued that the old (then current) model of energy caused the misconception that energy is ‘used up’. It was argued that a better model was needed that emphasised conservation of energy and treated energy as a single phenomenon, not multiple different substances.

Around 2007, the Institute of Physics promoted the energy stores and energy pathways terminology and formalised the new model. That was 18 years ago, so the new model is not really that new. Nevertheless, 2007 was after I finished my masters degree. I was busy working on (i.e. failing) my first PhD then. Many teachers of my generation were never exposed to the new model.

Energy is abstract. It is insubstantial. It is intangible. It is impalpable. It is best understood through analogies.

In 2011, the Association for Science Education promoted the new model in teaching guides. I had finished my teacher training at this point and had begun working in a leafy suburban boys grammar school near Manchester. While I was training in 2010, I remember deep discussions with my lecturers about this new model that was emerging. These discussions were after lectures, in a social context. When I trained to be a teacher, the old model was still widely being taught to new teachers; teachers who were training to be physics teachers but did not have a physics degree and so were being retaught the physics they’d forgotten since high school. I immediately saw the benefit of the new model.

Although in 2010 academies were no longer required to follow the National Curriculum (NC), in 2014 the NC was reviewed and changed to make energy conservation more central. This rippled into the specifications for the new GCSEs, so the current GCSEs are the first to include this new model, first examined in 2018.

What is energy?

The trickiest part of the whole model is answering the question, “what is energy?” This is especially true if someone has learned the older model.

Energy is abstract. It is insubstantial. It is intangible. It is impalpable. It is best understood through analogies.

People are usually familiar with another abstract, intangible, impalpable quantity: money. Money is not the metal discs or paper notes carried in a person’s wallet or purse, those are just symbols indicating who has the money. They are receipts of transactions. If I pass somebody a £5 note, I transfer £5 of my financial worth to them. The financial worth is not the £5 note, but the transfer of the £5 note allows us to track the transfer of financial worth.

I could transfer financial worth via another mechanism, such as a bank transfer. There is no exchange of a piece of paper with the King’s head on it, but nevertheless financial worth has been transferred.

Before 1931, those metal discs or paper notes were tokens representing how much of the country’s gold you owned. Since then, the value of money has been determined by government decree and public confidence; in other words, we all collectively believe that a piece of paper with the King’s head on it and £5 printed on it is worth £5, and we all collectively believe and agree what that £5 can buy. The financial worth of £5 is no longer tied to anything real, tangible, and palpable.

Most people accept the abstract concept of money because it is useful. They go about their lives happy to use this concept every day. People grumble they don’t have enough money and work hard to earn money even though money isn’t real. It’s taken to be provisionally real because of what can be done by transferring money. If money is transferred, things change. If money is transferred, things happen. When I go in a shop and transfer money, I go from having no vegan KitKat in my possession to gaining a vegan KitKat. When I get on a bus and transfer money, I go from being denied the ability to travel to the supermarket to being ferried there in the bus. When I pay my landlord money, I go from being in a state where they could make me homeless to one in which my shelter is secured. Money isn’t the important thing, the transfer of money is.

“Energy is ‘doing juice’ of the universe, giving objects the ability to make changes or do work.”

Energy is like this. It is an abstract quantity, just like money, which can be stored, just like money, and transferred, just like money. Things happen and situations change when energy is transferred. It is the transfer of energy that is interesting and important, not so much the energy stored. If there is insufficient energy stored for it to be transferred in a certain way, then the thing that would happen if the energy was transferred cannot happen. It is not a substance. But the transfer of this quantity causes things to happen and states to change.

- In Quantum Mechanics, the energy of a system is represented mathematically by the Hamiltonian operator operating on the wave function of the system. The square of the wave function of the system is the probability density function of the particles’ positions. So energy eigenstates in quantum mechanics are tied to probability.

- In General Relativity, energy is part of the stress-energy tensor (along with momentum, pressure and stress), which determines the curvature of spacetime, which causes what we perceive to be gravity.

- In Noether’s Theorem, each conserved quantity is caused by a continuous transformation of a system being symmetrical in some way. Energy conservation is caused by system changes under continuous transformation having time-symmetry (or time-translation invariance). I.e., a system’s evolution in time does not change if the whole process is shifted forwards or backwards in time, so the laws of physics do not change.

GCSE and A-Level students do not study energy to these levels, so when they ask “what is energy?” it can become difficult to answer correctly. Teachers end up saying things like “energy is ‘doing juice‘ of the universe, giving objects the ability to make changes or do work.” Statements like that risk giving the misconception that energy is a substance, but they have the benefit of bringing the focus on the changes that are occurring when energy is transferred. This is one of the main strengths of this new model: it focuses attention on what happens when energy is transferred, which is what physics is all about. The other strength is that the new model emphasises that energy is conserved. By transferring this abstract quantity, you don’t gain or lose it, it just moves out of one store and into another.

Importantly, the energy isn’t between the stores. As one store of energy decreases, another increases, but because energy isn’t a substance, it does not have to exist between the two stores. This is the reason I am not a fan of the term “pathways”, and prefer “transfers”, although even that term can cause the same misconception. I don’t teach transfer as “energy moves from one store to another”, I teach it as “one store loses energy and another store gains it”. This way, energy becomes less substantial.

The new model

So we are finally here. We have unlearned the old model and we are ready to learn the new one. Well done for getting this far! Even though energy is complicated and abstract, transferring energy is still a very useful way to approach physics, even for younger students, so we cannot just cut it out of the curriculum and leave it until university. UK exam boards have mostly agreed on this new model, albeit with slightly different wording between boards.

There are five energy stores (yes, there are more, but these five serve our purposes well at GCSE Level):

- Kinetic energy: energy stored due to a body’s motion

- Gravitational potential energy: energy stored due to a body’s position in a gravitational field

- Elastic potential energy: also called strain energy, energy stored due to temporary deformation of a solid

- Thermal energy: energy stored due to the temperature of the body

- Chemical energy: energy stored due to the possibility of exothermic chemical reactions

Not included on this list are: internal energy (thermal energy is part of this, but internal energy also includes energy stored due to the possibility of changing physical state and reducing enthalpy), electric potential energy (the electric field analogue of the gravitational potential energy), magnetic energy (the magnetic field analogue of gravitational potential energy), and pressure energy (the energy stored by gas in a vessel being held at higher pressure).

Nuclear energy is avoided because it causes confusion later on when A-Level students learn about nuclear binding energy. They often confuse the two.

The term heat energy is avoided because it is already messy enough with internal energy (which is part of GCSE but is not included in the list for the energy topic) and thermal energy. The word heat is used as a verb, rather than a noun. Heat isn’t an energy store, it is a process. To heat something means to transfer energy into its thermal energy store. I prefer to use the more verbose wording anyway to avoid confusion and discard the word heat altogether.

I have seen the term mechanical energy used when teaching, but I don’t recall seeing it on current GCSE specifications or on any current specification past papers. Please do let me know if I’ve missed something! Mechanical energy refers to the sum of the kinetic energy and potential energy stores (gravitational potential and elastic potential). It is a useful idea in A-Level where the energy of a simple harmonic oscillator and a damped oscillator are analysed, but I suspect the term will just cause confusion at GCSE Level. It isn’t an energy store, it’s a category of energy stores related to motion (hence the term mechanical). Given that mechanical work is another way of describing work done by forces, I think the term is best avoided.

Those five stores (kinetic energy, gravitational potential energy, elastic potential energy, thermal energy and chemical energy) are enough to be getting on with for GCSE level, but remember, they are not synonymous with the energy types (even if they share the same words), and the interesting bit is the energy transfers.

The energy transfer mechanisms (or pathways if you prefer, which I do not) are:

- Forces (or mechanical work)

- Waves (or radiation emission and absorption)

- Current (or electrical transfer)

- Heating (or conductive heating)

Work

I’ve mentioned work already. How can it be defined?

In the old model, we would say that ‘doing work means transforming energy from one form to another‘, and ‘energy is the capacity to do work‘. Oh dear. Without the new model, the definitions become circular. Many teachers teach the definition of work from the new model in a way that looks just as circular: ‘doing work means transferring energy from one store to another‘, and ‘energy is the capacity to do work.’

The definitions look circular because we have simply changed the wording from ‘transformation’ to ‘transfer’ and from ‘form’ to ‘store’. Remember the ocrawatt? Same problem.

Instead of saying ‘doing work means transferring energy…‘, we can say that energy is transferred when work is done. The doing of work takes centre stage, and transfer of energy is a consequence of the work being done. It’s a subtle distinction, but it removes the circularity of the definitions! Now, energy is simply a system of accountancy, a zero-sum game. The sum of all the energy stores in a system before work is done is equal to the sum of all the energy stores in the system after work is done. Energy is conserved. But we are still no closer to saying what work is. We need a few more technical words first. Let’s build up our definition of work (without needing to mention energy) step by step.

- A system is a set of interacting bodies

- A system’s state is a complete set of physical conditions or properties that define the system at a given moment

- Doing work means changing a system’s state

So altogether, doing work means causing a change in the complete set of physical conditions or properties that define a set of interacting bodies.

For example, if a body’s speed changes, work has been done. If a body’s temperature changes, work has been done. If a body changes from one physical state to another (i.e. solid, liquid, gas, or plasma), work has been done.

Note that I use the term physical state to refer to the state of matter (solid, liquid, gas, or plasma) rather than just state to reduce ambiguity and confusion. A system’s state can change when there is a change of speed of bodies in that system, or temperature, or physical state, or charge density, or pressure, or volume, or any other condition or property that describes the system at that moment.

Each condition or property of a system has a corresponding energy store that is quantifiable, but the energy is abstract, whereas speed and temperature and physical state are not.

When there has been a change in the state of the system, work has been done. The changes in energy stores is the quantification of the work that is done. When a ball is thrown upwards and ascends without being pushed, its speed reduces. This is a change in the system’s state, so work is being done. We can quantify how much work is done, which we measure in joules. We say that the kinetic energy store of the ball has reduced, and the gravitational potential energy store of the ball has increased, and the amount the two stores of energy have changed by is equal to the work that has been done, so the total energy in the system remains constant.

Of course, these energy stores do not really exist, they are abstract, just like money does not really exist. It is often convenient for problem solving to calculate how much work has been done by calculating changes in energy stores, but they are abstract, intangible, and impalpable.

In short, energy is just a convenient problem-solving hack, and the new model shifts focus from saying things happen because of energy transformations (which is just not true) to saying things happen because of external influences. The processes causing changes in a system’s state matter because that’s what physics is really describing!

Work done by a force

If a resultant force acts on a body in the direction the body is moving, then the body’s speed increases. If a resultant force acts on a body in the opposite direction to the direction the body is moving, then the body’s speed decreases. In short, resultant forces change motion. We can quantify motion as momentum, the product of mass and velocity. A resultant force can change the momentum of a body without increasing its speed if the resultant force is perpendicular to the momentum. Work is only done by the resultant force if the speed of the body changes, which only happens if there is a component of the resultant force parallel to the momentum.

Forces can also do work if two or more forces act on the same body to cause it to change shape. If the change of shape is temporary, then when the forces are removed the body returns to its original shape and we say the body was elastically deformed. The elastic forces that cause the body to return to its original shape also do work.

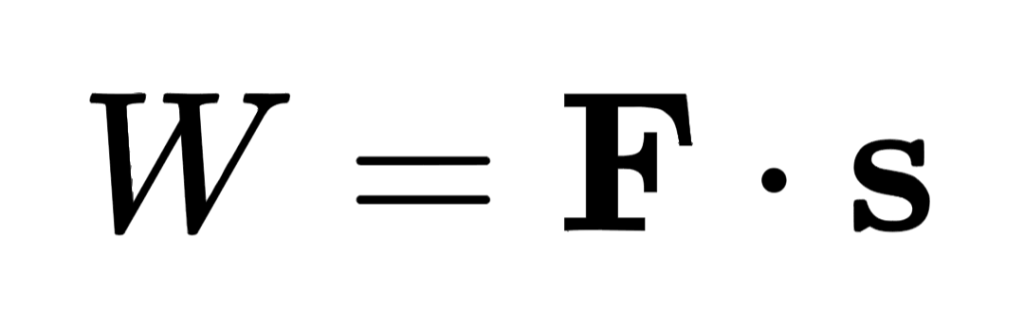

The work that is done by a constant force is W=F•s. If there is no movement parallel to the force, there is no work done by the force. If the force depends on the displacement, then the work done is:

Work done by waves

All bodies emit electromagnetic radiation. At low temperatures, only infrared radiation is emitted. At higher temperatures, shorter wavelength electromagnetic radiation is emitted, and the intensity of emitted radiation increases. When a body emits electromagnetic radiation, its temperature reduces. We can say that its internal energy stores reduce (if there are no physical state changes, then it’s the thermal energy store that reduces).

At this point it’s worth mentioning that the emission spectrum from black bodies only depends on the temperature of the body; that is one way we define black bodies.

When a body absorbs electromagnetic radiation, its temperature increases. We can say that its internal energy stores increase (again, if there are no physical state changes, then it’s the thermal energy store that increases).

Very often ‘the surroundings‘ are one of the bodies in our system. A cup of peppermint tisane with water straight from the kettle is at a higher temperature than the surroundings. The rate that the thermal energy store of the cup reduces due to emission of infrared radiation is greater than the rate that the thermal energy store of the cup increases due to absorption of infrared radiation. The infrared radiation absorbed by the cup is what was emitted by the surroundings. The infrared radiation emitted by the cup is absorbed by the surroundings. The rate that the thermal energy store of the surroundings increases due to absorption of infrared radiation is greater than the rate that the thermal energy store of the surroundings decreases due to the emission of infrared radiation. This statement about why the temperature of the cup of warmer peppermint tisane decreases and the temperature of the cooler surroundings increases in terms of energy changes is deliberately verbose to reduce ambiguity, but it does make it difficult to follow. One may have to read it several times to understand it.

With this new model, the emission and absorption of electromagnetic radiation by a body causes temperature changes of that body depending on whether there is more emission than absorption or the other way around. When there is more emission than absorption, the temperature of the body decreases. When there is more absorption than emission, the temperature of the body increases.

This is how it really works! The cup of peppermint tisane does not know it is at a higher temperature than the surroundings, so energy has to flow out of it, which is how it may have been worded using the old model. Rather than talking about energy flowing, we talk about the processes causing state changes in the system. In this case, the state changes are temperature changes (note, ‘state‘ is not synonymous with ‘physical state‘. See above. As an aside, I would rather talk about the phase of matter rather than the physical state of matter, it is more general and less ambiguous, but phases of matter are not included in GCSE or A-Level specifications.)

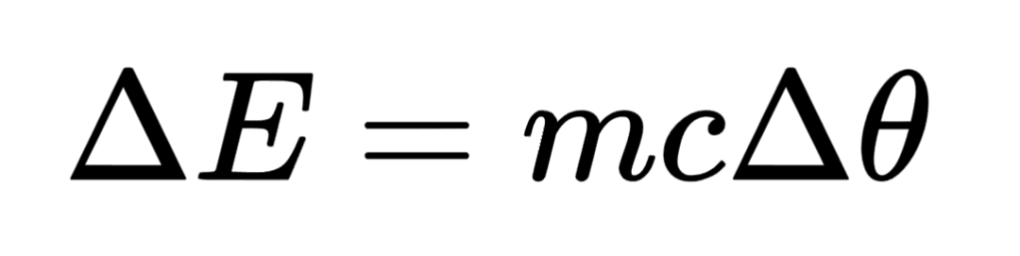

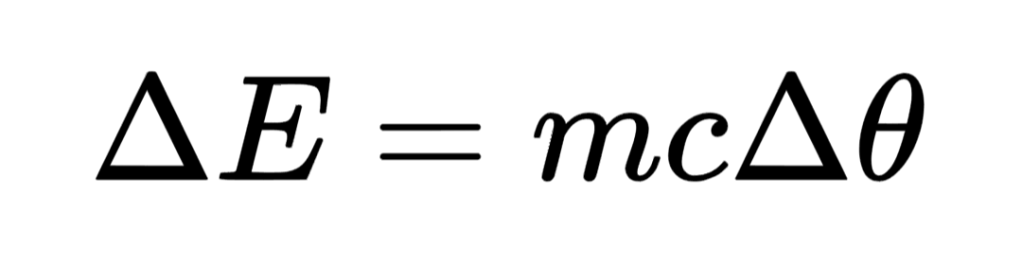

The net change in the thermal energy store of a body can be calculated based on the temperature change of the body using this equation:

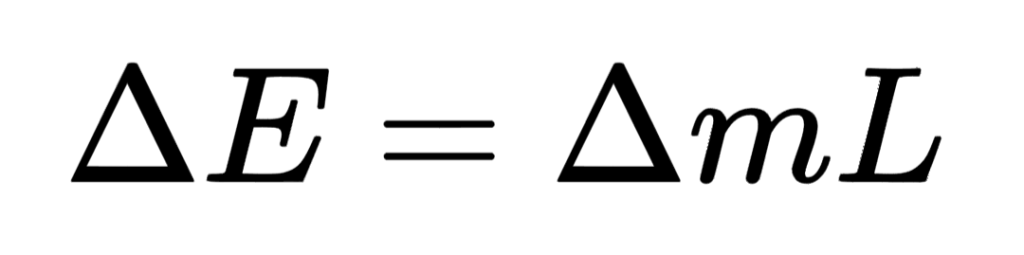

If the body undergoes a change in physical state, we can use this equation:

Together these two equations describe changes to the internal energy stores of a body.

Electromagnetic radiation emitted from one body will be absorbed by another (even if that other body is ‘the surroundings‘) so the decrease of one energy store corresponds to the increase of another, and energy is conserved. The problem comes when describing someone using a laser device to shine laser light up into space (or something similar). Visible light is part of the electromagnetic spectrum, so the energy stores of the laser device reduce due to the emission of this light. Ultimately, it will be the chemical energy store of the batteries in the laser device that reduces, with a series of processes involved in producing the laser light beam. What absorbs that light? Well, it could be a celestial body many light years away, or it could be nothing at all! Teachers must avoid saying things like ‘energy is still conserved because the light energy is moving away from the laser‘ even if this is the easy answer because it produces the misconceptions that the old model produced.

Coupled oscillating electric and magnetic fields (which is what electromagnetic radiation is) cause the transfer of energy, yes, and we can use the Poynting vector to calculate the energy transfer per unit vector-area per unit time, but that is beyond the scope of A-Level physics courses. Light is not a store of energy, and the new model places emphasis on the processes of doing work, not the energy changes themselves. In the case of electromagnetic radiation, the process involves solving Maxwell’s equations, which (you guessed it) are beyond the scope of A-Level physics courses.

It is not necessary to invoke a myth of ‘light energy‘, it is sufficient to say the energy stores of a body reduce due to emission of radiation. Energy is still conserved, but the other half of the energy conversion is not always known if the system is so large (such as shining laser light into the depths of space). The energy is not destroyed, but who knows what energy store will increase? It could be a nebula, a star, a black hole, or maybe the heat death of the universe itself. At that stage, we realise that energy is not conserved after all because of the accelerated expansion of the universe, and that leads to bigger questions about cosmology and the nature of energy conservation. If you are interested, look up what Noether’s Theorem says about time-translation invariance being violated by universal accelerated expansion. It may be easy to say energy is still conserved when a laser light is shone deep into space, but that does not make it true. I think it is best to avoid telling young people lies for the sake of ease unless it is absolutely necessary, and in this case I do not think it is.

So might for electromagnetic waves, what about sound waves? They are of a different nature to electromagnetic waves. Sound waves are mechanical, whereas electromagnetic waves are not. Sound waves are longitudinal, whereas electromagnetic waves are transverse. Sound waves require matter, whereas electromagnetic waves do not.

Sound waves, just like electromagnetic waves, are a mathematical description of a process that transfers force without transferring matter. Just like with electromagnetic waves, sound waves are not a body, not an entity, not a thing, so they cannot store energy.

When a body emits a sound wave, its energy stores reduce because work is being done by pushing the medium that is carrying the sound wave. This is no different to work being done by a force; that is precisely what is happening. Because sound waves (and any acoustic waves, including seismic waves) require a medium, the motion of the matter in the medium is changed by forces. We say the energy dissipates; what we mean is that the thermal energy store of the surrounding matter increases due to the absorption of sound waves.

With all waves, emission causes a decrease in a body’s stored energy, absorption causes an increase in a body’s stored energy. The nature of these changes, the nature of the work being done, is ultimately no different to the nature of forces doing work; although, with electromagnetic waves it is electric (and magnetic) fields that oscillate and the forces are only produced when electric charges are present. Similarly, gravitational waves are oscillations of the gravitational field and mass must be present for there to be forces.

The old model works, sure, and it may be easier at first glance, but it posits a fake mechanism that occults the physics taking place. The new mechanism has scope to be extended right to the frontiers of physics without inventing fake mechanisms, and is not too difficult to follow if it is navigated carefully in terms of energy transfers. I think the emission and absorption of waves really highlights the benefit of the new model, along with how the new model explains electricity.

Work done by a current

In a simple circuit with a battery and a lamp, the old model taught that chemical energy from the battery transforms into electrical energy in the wires, which then transforms into thermal energy in the lamp and is then transformed into light and heat energy emitted from the lamp. Students are often taught that charge moving through a battery gains electrical energy and that charge carries that electrical energy to the lamp. This is incorrect.

Firstly, what is the electrical energy? Some young people will explain it to themselves as being the kinetic energy of the electrons. It is easy to demonstrate that that view is incorrect. If it were so, electrons would leave the lamp slower than they entered it, so we would accumulate electrons in the lamp and the lamp would become negatively charged. It does not.

Secondly, how does the electrical energy get from the battery to the lamp? If electrical energy is carried by charges, then the charges would need to travel from the battery to the lamp to deliver that energy. The charges moving in the simple circuit described above are electrons. Electrons drift through a simple circuit at speeds of tens of microns per second, around 10-50 µm/s. That means the distance travelled by electrons in a circuit is, on average, the thickness of a human hair per second! If electrons needed to travel from the battery to the lamp to deliver the electrical energy, it would take a long time for the energy to actually get to the lamp!

Some young people think that the electrons push on the electrons next to them, so just like Newton’s cradle the motion of the electrons is transferred instantly from the electrons near the battery to the electrons near the lamp. That view still begs the question, what is that energy then? If it is the kinetic energy of the electrons, we still have the same problem of the model accumulating charge. The electrons do push each other, but they are able to change their distance from each other, so it would be like trying to set up Newton’s cradle with soft squashy plastic balls; it wouldn’t work.

Someone who has learned the old model may find it difficult to accept the new model. That is one of the reasons it is so important to get it right the first time it is taught!

Clearly, the old model is broken beyond repair here. So how does energy get from the battery to the lamp?

If someone asks that question, it exposes their misunderstanding of energy transfers. Energy transfer is not energy moving. The energy does not move from battery to lamp; rather, the energy store of the battery decreases and the energy store of the lamp increases, and the same process that reduces the energy store of the battery also increases the energy store of the lamp (this is why I do not like the term energy pathway). It is a subtle difference, and someone who has learned the old model may find it difficult to accept the new model. That is one of the reasons it is so important to get it right the first time it is taught!

When exothermic chemical reactions happen in the battery, the chemical energy store of the battery decreases. Those chemical reactions involve the transfer of charge (all chemical reactions involve charges moving), so if there is no current through the battery, there is no transfer of energy out of the chemical energy store of the battery. In physics we are less interested in the electrochemistry, so it is sufficient to say that a current through the battery is necessary to cause a decrease in the chemical energy store of the battery.

When there is a current through the lamp, the electrons that are flowing interact with the ions in the metal. The collisions between electrons and ions transfer energy to the ions, increasing the thermal energy store of the lamp. We have already discussed how increasing the thermal energy store of the lamp caused light to be emitted, so I will not go into that again.

Here is the tricky part, if the electrons transfer energy to the ions to increase their average energy (increasing the temperature of the metal filament in the lamp), then does that mean the electrons emerge with less energy? Well, yes, but there is no net reduction of the electrons’ kinetic energy stores.

Electrons move from a high electric potential to a low electric potential (actually from a more negative to less negative electric potential, because electrons are negatively charged, but electric potential is not studied formally until A-Level physics, so it is easier to visualise what is going on if we just talk about ‘higher and lower electric potentials’ and ignore the sign for now). What is electric potential?

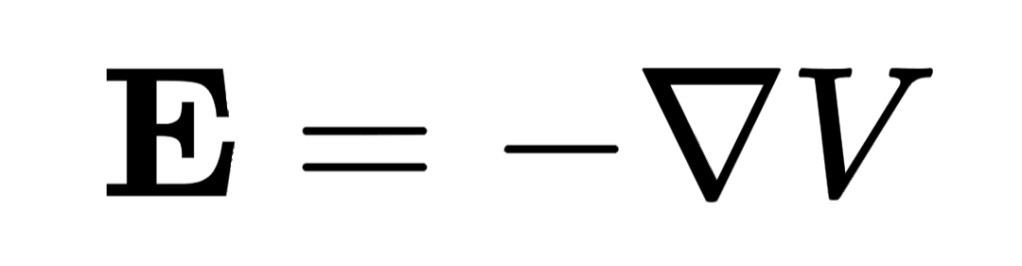

Electric potential is a way of quantifying the electric influence of an electric field on an electric charge. The other way of quantifying electric influence is with electric field strength. The two quantities (electric potential and electric field strength) are closely related, but electric potential is a scalar and electric field strength is a vector. For those who enjoy calculus, the electric field strength is equal to the negative of the electric potential gradient, that is to say, the negative of the first derivative of electric potential with respect to distance (in one dimension. In two or three dimensions, we have to use the vector gradient operator ∇, nabla, making electric field strength a vector.) The electric field strength is:

Teaching the new model makes the transition at A-Level easier.

Electric field strength is an easier quantity to understand. It quantifies the electrostatic force (due to the electric field) experienced by a positively charged body divided by its charge. Electric field strength is therefore directly related to the force on a charged body. It is quantifiable. Forces cause changes in velocity, so forces do work, as already discussed. In a circuit, the force on an electron is proportional to the product of the electric potential gradient multiplied by the charge of the electron. If there is a difference in electric potential across the lamp (a potential difference, also colloquially called a voltage, but I prefer the term ‘potential difference‘ because it more closely describes the physics), then there is a non-zero potential gradient, therefore a non-zero electric field strength, which causes the electrons to experience a force.

Of course, electric fields are abstract, electric field strength is abstract, and electric potential is abstract, but so is energy. We can use an instrument called a voltmeter to measure the difference in electric potential (the potential difference) across a component. If there is a potential difference, then there will be an electric field strength causing a force on charges. If those charges are able to move, their motion can be changed by the electrostatic force, so work is done.

Why do the free moving charges (the electrons in our circuit) not just accelerate forever if they are experiencing an electrostatic force? Because the electrons interact with the metal ions, they collide. Each collision between an electron and an ion causes the electron’s velocity to reduce and the ion to gain velocity in the direction of the collision. We can say the electron’s momentum is reduced and the ion’s momentum is increased by the same amount, but momentum is abstract. We can say the kinetic energy store of the electron reduces and the energy stores of the ion increase, but energy is abstract too.

If the kinetic energy store of the electron was to reduce at a greater rate than the electrostatic force causes it to increase, then the electron would slow and eventually stop, which does not make physical sense because it would cause the accumulations of charge in the circuit. If the kinetic energy store of the electron was to increase because of the electrostatic force at a greater rate than it reduces due to collisions with the metal ions, then the electron’s average speed would increase. The increase in average speed of the electron increases the frequency of collisions between the electron and metal ions, thus increasing the rate that the kinetic energy store of the electron would reduce. The electron reaches a power equilibrium, where the rate of increase of its kinetic energy store due to the electrostatic force is equal to the rate of decrease of its kinetic energy store due it colliding with ions.

Higher potential differences correspond to higher electric field strengths. The rate of transfer of energy to the ions depends on the electric field strength, because higher electric field strength means more force on the electrons, which means greater acceleration of electrons, which means greater rate of the electrons’ kinetic energy increasing, and as the electrons’ speed increases the rate of collisions with ions increases, increasing the rate of the ions’ energy stores increasing, increasing the rate of increase of temperature of the metal.

The electrons do not carry the energy to the lamp because the electrons are already in the lamp. The rate that the electrons’ kinetic energy increases is equal to the rate it decreases, so there is no net change in the kinetic energy stores of the electrons.

Would you teach all this to Key Stage 3 or Key Stage 2 pupils? Of course not!

Why does the temperature of the metal not increase infinitely? Because of energy transfer by waves, as already discussed. The metal reaches a power equilibrium where the rate of energy transferred to the metal by a current is equal to the rate of energy transferred out of the metal by waves. Thus, the higher the potential difference across a lamp, the brighter it is. You can clearly see the benefit of the energy stores and transfers model (the new one) over the energy types and transformations model with the example of the simple circuit!

Now, the mechanism for how electric fields behave in a circuit requires understanding of the interrelationship between electric fields, currents, and magnetic fields. Students would have to understand and know how to use Maxwell’s Equations to fully grasp electricity (and I teach that to my Year 13 students). Would you teach all this to Key Stage 3 or Key Stage 2 pupils? Of course not! All they have to understand is that there would be no reduction of the chemical energy store in a battery without a current, and no increase in thermal energy store in a lamp without a current. Current is the mechanism for transferring energy electrically. That is the new model! And the new model is entirely compatible with the deeper mechanisms that use Maxwell’s Equations, whereas the older model is not. Teaching the new model makes the transition at A-Level easier.

Work done by heating

The fourth transfer mechanism is conducive heating. Heating here is not referring to the transfer of energy by absorption and emission of infrared radiation, which colloquially is often called heat. To reduce confusion I add the adjective ‘conductive‘ to conductive heating, or the adverb ‘conductively‘ to the verbal phrase conductively heat. The transfer of infrared radiation type of heating was already included in the transfer of waves mechanism.

Heating here is also not referring to convective heating. Convection is where a lower temperature fluid contracts, becomes more dense, and sinks beneath a higher temperature fluid, displacing it upwards. Convection is the physical movement (the physical flow) of matter. The flowing matter carries the higher temperature fluid upwards against gravity, so energy is transferred only because the matter storing the energy is transferred. Not all UK exam boards include convection now at GCSE level (only the CIE and Edexcel IGCSE Physics courses and the WJEC GCSE Physics course still include it), because the mechanism does include flow of a substance, and it is too easy for young people to gain the misconception that all heating involves the flow of heat, as if heat is a substance. I already addressed the issue of using the word heat as a noun earlier in this article. I still teach convection anyway because it is necessary for understanding why trapped air is a better insulator than just an air gap, but that level of detail will not be examined.

If two bodies at different temperatures are in thermal contact with each other… there is a net decrease in the thermal energy store of the higher temperature body and a net increase in the thermal energy store of the lower temperature body.

The three traditionally taught heating mechanisms are conduction, convection, and radiation, with evaporation sometimes being included on the list (energy transfers causing physical state changes was addressed earlier in this article too). Once we subsume heating by radiation in the mechanism of energy transfer by waves and discard heating by convection and heating by evaporation, all that is left is heating by conduction.

The short version is: if two bodies at different temperatures are in thermal contact with each other, then over time there is a net decrease in the thermal energy store of the higher temperature body and a net increase in the thermal energy store of the lower temperature body until the two bodies are at the same temperature. Yes, that’s the short version. Any shorter and you risk creating the misconception that energy moves from one place to another as a substance. We can get away with saying energy is transferred from high temperature bodies to low temperature bodies only if the concept of transfer has been understood; it isn’t moving from one place to another via the path in between, it is ceasing to be in one place and commencing being in another. Once again, this is my objection to the use of the term pathway. I digress.

The conductive heating mechanism is ultimately about collisions between particles in a substance, and collisions between two particles are caused by forces between them, so this energy transfer mechanism is no different to the transfer of energy by forces on the smallest scale. The reasons why it is beneficial to treat conductive heating separately are because a), there are too many particles in a substance to keep track of, with too many individual interactions, and b) we are able to describe conductive heating mathematically, so there would be little benefit at GCSE Level or A-Level to going into too much detail about the mechanism.

I refer to particles rather than molecules because particle is a more general term. The smallest unit of matter is a particle. Exempli gratia, a particle of water is a molecule of H₂O, a particle of iron metal is an ion of iron, a particle of helium gas is an atom of helium, a particle of cathode ray is an electron, a particle of alpha radiation is a helium nucleus, and so on. Examination board specifications may use the term molecule where it would not necessarily be appropriate. All molecules are particles but not all particles are molecules.

At a particle scale of individual interactions, Newton’s third law means that the gain of momentum of one particle is equal to the loss of momentum of the other particle. When particles have the same mass and the collisions between them are elastic, the momentum of each particle is swapped; this is a consequence of conservation of momentum. Ions that are in fixed positions in a solid metal collide with their neighbours. If one part of the metal is at a higher temperature, those ions have a higher average speed, so have a higher average momentum. As collisions cause momentum to be transferred and because there are so many particles that are colliding, statistically the net transfer of average momentum is from the particles in the higher temperature matter to the particles in the low temperature matter.

Here, we have to be careful what is meant by average. The mean momentum of particles in a stationary body is zero, but the root-mean-squared momentum is not zero as long as the temperature of the body is above absolute zero (which it will be). This is because momentum is a vector quantity. Averaging vector quantities has to be done carefully to take into account the quantity’s direction. Root-mean-squared averages are taught to A-Level students, not GCSE pupils, so it is best to use the vague word average for now.

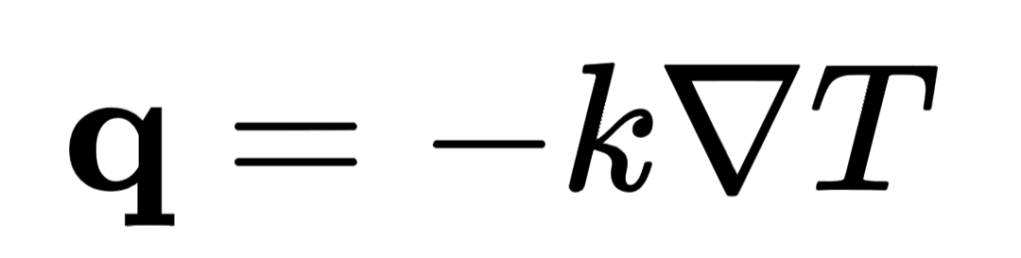

The rate of energy transfer by conductive heating per unit cross sectional area (also called heat flux) is proportional to the conductivity of the medium and also proportional to the temperature gradient across the medium. So, a greater temperature difference across a certain length of body will cause a greater rate of energy transfer; the same temperature difference across a smaller length of body will cause a greater rate of energy transfer; the same temperature difference across the same length of a more thermally conductive body will cause a greater rate of energy transfer. The heat flux is given by:

where k is the thermal conductivity and ∇T is the vector gradient of the temperature.

What should be taught to pupils?

To GCSE pupils, I would start by teaching the four mechanisms for changing motion, and I would avoid references to energy at first. Movement of the particles that constitute a macroscopic body is associated with the temperature of the body, so these four mechanisms either change the macroscopic motion of a body or change its temperature.

- Forces: forces either change the momentum of a body, or change the body’s shape. The change in momentum can be linked to Newton’s second law; the rate of change of momentum is equal to the resultant force. The change in shape of a body can be permanent (plastic deformation) or temporary (elastic deformation).

- Waves: absorbing waves causes the average momentum of the particles in a body to increase, increasing the body’s temperature. Emitting waves causes the average momentum of the particles in a body to decrease, decreasing the body’s temperature. This is true for electromagnetic waves, sound waves, or any other waves. Essentially, waves are a mechanism for transmitting forces without transmitting matter. The movements of individual particles in a body are impossible to track because there tends to be so many of them. On the macroscopic scale, higher average momentum of particles (and therefore higher average speed of particles) is associated with higher temperatures, and vice versa.

- Electric currents: chemical reactions can cause charges to move, causing electric currents. Moving charges (usually electrons) can also transfer momentum to metal ions by colliding with them, so currents increase the average momentum of the ions, increasing the temperature of a metal. Electric current links chemical reactions of a cell in one part of a circuit to the increase in temperature of a metal filament of a lamp in another. It is best to avoid electromagnetic devices such as motors or buzzers at this stage, but if it comes up, moving charges are the driver of a change of a system’s state.

- Conductive heating: if two bodies are in thermal contact and are at different temperatures, then collisions between particles in the bodies causes the temperature of the higher-temperature body to decrease and the temperature of the lower-temperature body to increase.

Then I would introduce the idea of work (measured in joules) as an abstract quantity that is transferred by the four mechanisms above.

- Forces: work is done, equal to the product of the force and the parallel displacement of a body.

- Waves: work is done by a body when it emits waves, and work is done on a body when it absorbs waves.

- Electric currents: work is done when there is a current through a component with resistance, which causes an increase in temperature. One way to produce currents is with chemical reactions in cells connected in a circuit. The rate of work being done by a current passing through a resistance is:

- Conductive heating: work is done by high temperature bodies on low temperature bodies, causing the temperature of the higher-temperature body to decrease and the temperature of the lower-temperature body to increase.

Work being done causes changes in momentum, shape, or temperature, and allows us to quantify the changes.

Then I would introduce the five energy stores. When work is done, energy is transferred from one store to another. The energy is abstract, but by quantifying it we can calculate changes in energy stores. A change in an energy store is equal to the work that is done by the transfer mechanism. The amount of stored energy is the capacity to do work. If there is more energy in a particular store, more work can be done to transfer the energy out of that store, into a different store.

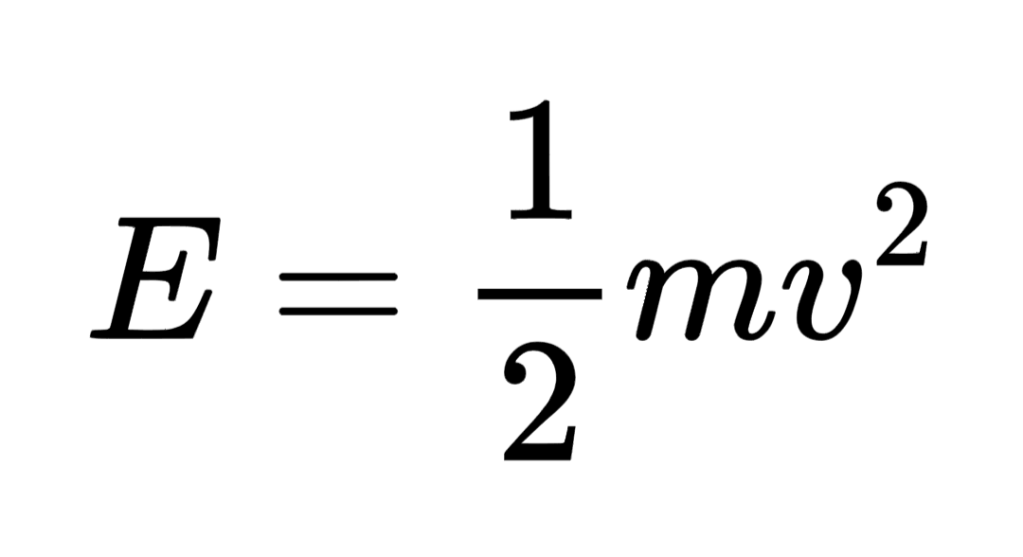

- Kinetic energy store: the energy store associated with the movement of a body:

- Gravitational potential energy store: the energy store associated with the height of a body in Earth’s gravitational field:

- Elastic potential energy store: the energy store associated with temporarily changing the shape of a body:

- Thermal energy store: the energy store associated with the temperature of a body:

- Chemical energy store: the energy store associated with endothermic and exothermic chemical reactions.

Work always has two sides: the decrease of one energy store and the increase of another. The magnitude of the decrease in one energy store is equal to the magnitude of the increase in the other energy store, but it is the same mechanism reducing one as increasing the other.

This is called conservation of energy. The total energy in an isolated system remains constant.

Energy transfers between stores becomes a useful model; a shorthand for the mechanisms that are occurring.

At A-Level, the concepts can be expanded. Calculus can be used to calculate work done where forces are not constant, gravitational and electric fields are understood in more depth, thermal physics is treated more rigourously, quantitative electromagnetism is explored, and quantum mechanics and special relativity are introduced. In short, we build on the GCSE model. It does not have to be cast aside or discarded, students are not told ‘we lied to you at GCSE Level‘, and so A-Level Physics becomes more accessible. There is no downside.

Teaching energy stores in the lab

Here’s a video where I talk about energy stores. I hope you find it useful!

And another video where I talk about energy transfer by a current

Follow me on WhatsApp for updates, click here or scan the QR code below.

Reminder: Weekly Live Tuition Sessions!

SATURDAY 14th March 2026

| GCSE Physics | 9:30am | Generator effect |

| A-Level Physics | 10:30am | Multiple choice questions |

| GCSE Astronomy | 11:30am | Exploring starlight (1) |

If you wish to enrol on the tuition sessions and haven’t yet, then click enrol below

I’m curious, what methods do you think work best for teaching energy to high school students who struggle with abstract concepts?

LikeLike