As an experienced AQA A-Level Physics examiner, there are a few issues I see crop up year after year. Students can gain marks with a little tweaking to their examination technique. Here are five exam technique tweaks that could get you extra marks and push your grade higher.

5. Significant figure inconsistencies

You used numbers in your calculation provided by the examiner. Each number was expressed to a certain number of significant figures. They may all be the same number of significant figures, but not always. Whatever datum used in your calculation that has the lowest number of significant figures, that is what determines how many significant figures your answer should be rounded to. Just before writing the answer on the answer line, you should write the answer with at least one or two additional significant figures. If you need to use your calculated answer to one part of a question in a subsequent part, use the one that is rounded less (the unrounded number, or the one to more significant figures than the final answer was). This is crucial to avoid the accumulation of round off errors.

Examiners will sometimes be given a few possible correct answers on the mark scheme, but each correct answer corresponds to the number of significant figures used in the calculation. To ensure you don’t lose marks unnecessarily, write down the numbers you are using, and use those numbers (not what is stored in your calculator).

But be careful of integers. The concept of significant figures does not apply to small integers. If you measured the time for 5 oscillations, that does not mean the time period would be correctly expressed as one significant figure!

Never give answers as fractions or surds. I know I know, the mathematics department tells you to use simplified fractions and surds where possible, but in PE you throw spears, and that’s not appropriate in physics either; in English you quote Shakespeare, don’t do that in Physics exams; in Geography you colour stuff in a lot, physics papers are scanned in black and white; in art it’s considered expressive to use your hands to smear paint over the paper, whatever you do, do not do that in a physics exam. The expectations are different for different subjects. Mathematics and Physics are not the same (the latter being obviously superior).

Physics is concerned with physical reality. It deals with what is measured. Measuring instruments inherently have uncertainties. Expressing an answer to the wrong number of significant figures (or worse, as a fraction or a surd) is like making stuff up, inventing data. You don’t know a measurement to an infinite number of significant figures, so you cannot know the result of a calculation to an infinite number of significant figures either.

You can train yourself to be more fastidious with significant figures by regularly using Isaac Science resources.

4. Poor diagrams and graphs

Sharpen your pencil. Use a 30cm clear plastic ruler. Not a 15cm opaque one. Not two 15cm opaque rules connected with a hinge because it more conveniently fits in your pencil case. Certainly not a roll-up ruler (it’s designed to bend, how is that any good for drawing straight lines?). Not the flat edge of a half-snapped protractor! Get yourself equipped properly. A fresh sharp HB pencil, sharpener on standby, and a 30cm clear plastic ruler. Why a fresh pencil? The graphite inside pencils is brittle, so as they bang around in your pencil case the graphite shatters and it becomes challenging to sharpen them (the tip keeps breaking off). Why a 30cm ruler? The diagonal length of a paper is about 36cm, so the drawing space is often more than 15cm diagonally. Why a clear plastic ruler? So you can draw lines of best fit and see the points the ruler would otherwise block.

Make diagrams large. As large as possible. Scale diagrams in particular should be as large as fits in the space with a sensible scale (1N:5cm, fine. 1N:4.6cm, that’s a bit daft).

Exam papers get scanned, and the scanner quality is terrible. You need to make sure everything is large and clear. If lines are supposed to connect, make sure they do. If a curve on a graph is supposed to touch the x-axis, make sure it does.

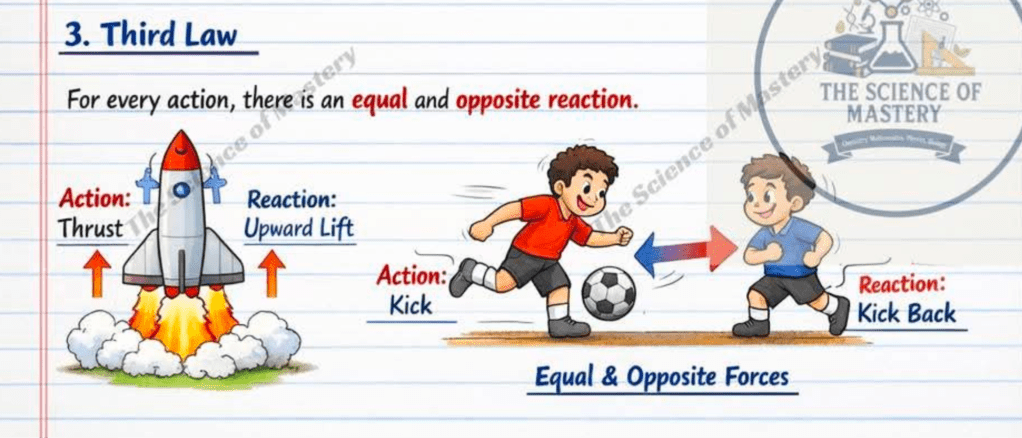

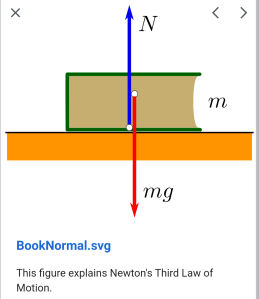

3. Newton’s Third Law

Not number 1 on my list, because this only affects a few topics, but it crops up again and again. For example, when measuring flux density, a current carrying wire produces a magnetic force on a permanent magnet, which is resting on a balance. What direction does the current go through the wire? So many students will forget that if the balance is being pushed down by the magnetic force on it from the wire, then the wire is being pushed up by the same force. If the question needs an explanation for the direction of the current, don’t forget to state Newton’s Third Law. See the command word section below.

And let’s never forget that most people simply don’t understand Newton’s Third Law or confuse it with Newton’s First Law! AI does this:

Wikipedia has this:

Even flashy physics revision videos with excellent production values and almost a million views, from YouTubers with over four-million subscribers, produce nonsense like this:

Most people don’t get it. Don’t worry, I can help you. I don’t have the flashy animations or high quality microphone or expensive camera, but I do have physics knowledge. Check out this video:

2. The power of 10 and unit traps

Physics deals with the unimaginably large and the unimaginably small. Mass of an electron? It’s about 0.000000000000000000000000000000911kg. Distance between the Earth and the Sun? A much more manageable 150000000000m. Use standard form! The extreme examples make it obvious, but when magnetic flux density tends to be given in millitesla, that’s where students start to mess up, or when graphs show s/10²m, that means each value along that axis is a bare number you must multiply by 10²m to get the displacement. Don’t forget that 10² when calculating gradients or intercepts!

Power of ten mistakes occur in one of three ways. Either the student has not taken into account a unit prefix (or got it wrong. Even Year 13s in the stress of an exam can mistake pico for femto, or giga for tera), the student did not notice the power of ten written (or forgot to include it in the calculation), or the student made a mistake transcribing the number (either from the paper to the calculator, or from the calculator to the paper.) The last of these is usually because the student is trying to count how many zeroes are on the screen. Just set your calculator in “sci” mode (scientific notation, also known as standard form) and that problem goes away.

1. Ignoring command words

This is the big one! Often students try to write an explanation for a question that requires them to describe what is happening, so they waste valuable time and space on the paper. Often students give descriptions and not explanations for an explain question. The worst command words mistake is students failing to understand what show that means.

If you are told to describe something, just write what you see, what happens, and what changes occur, but do not say why it happens.

The explain command word requires you to say why something happens, giving physics reasons. For example, if asked to explain why a kicked ball is in the air for a certain time, the answer would be about the vertical component of velocity, not the intention of the sports-person to make the ball land in a particular place. Another example, if asked to explain why a motor in an electric vehicle spins more quickly when more current passes through it, the answer cannot be because the motor makes the car go faster, and the speed limit may have increased, instead the idea of greater flux density from the current and therefore stronger magnetic forces, more moment, and thus greater angular acceleration would be the physics reasons.

As I mentioned, show that questions cause considerable problems, but there are a few things to remember. Always show all steps, including the starting points (any equations you’ll be using and any assumptions you make in using them). It is best to work algebraically first for these types of questions or you risk getting lost. Show all steps. Whatever you are asked to calculate, make that the subject algebraically. Then substitute and compute the answer to at least one additional significant figure compared to what was in the question. Annotate your working. Show that does not mean convince yourself that, the command word show that is testing your ability to communicate scientifically; to teach. In show that questions, imagine you are trying to explain something to someone who is clever enough to understand, but lacks the knowledge.

Bonus mistake: vagueness

Look out for examiners being vague in questions, and avoid vagueness wherever possible. Don’t just say a quantity changes, does it increase or decrease? Don’t say “faster” or “slower”, say increased rate or decreased rate (if referring to something changing over time). If you see the word change in a question, there’s often an easy mark for saying which way the change goes.

Reminder: Weekly Live Tuition Sessions!

SATURDAY 28th February 2026

| GCSE Physics | 9:30am | Motor effect |

| A-Level Physics | 10:30am | Electromagnetic induction |

| GCSE Astronomy | 11:30am | Formation of planetary systems (1) |

If you wish to enrol on the tuition sessions and haven’t yet, then click enrol below